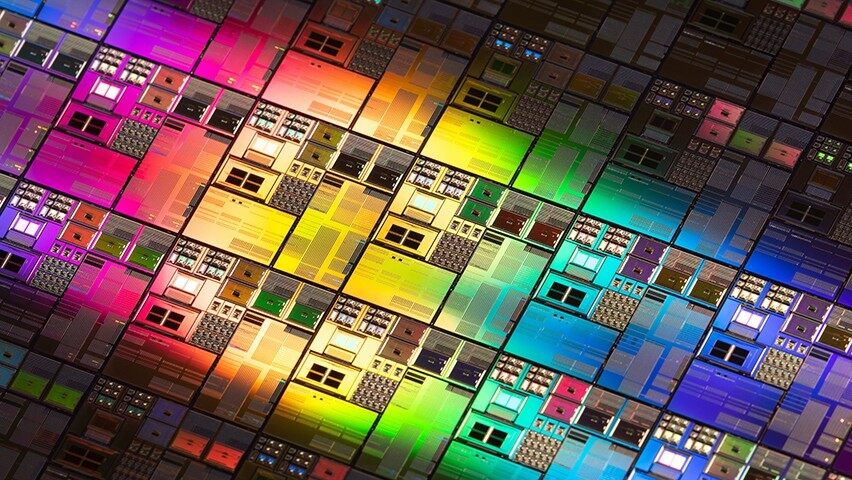

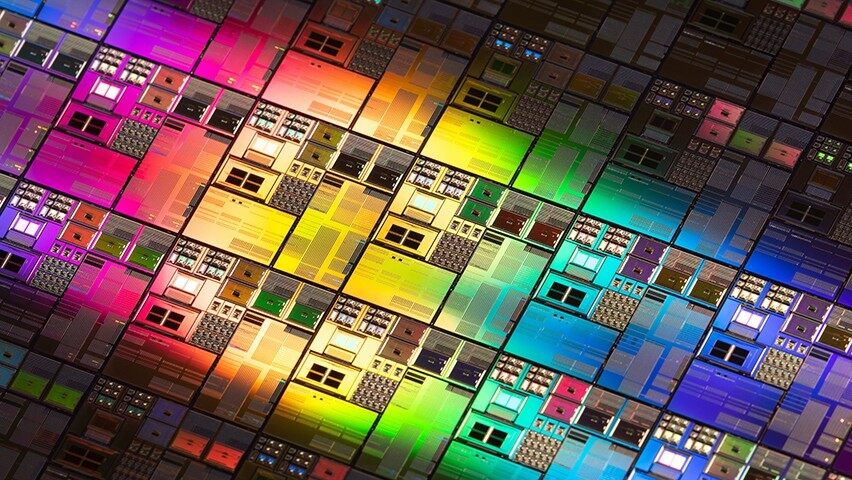

Semiconductor chips are among the most complicated man-made creations you can name, powering everything from your smartphone and laptop computer to the increasingly sophisticated appliances in your home.

We know how these chips work. But as they have become more complex, chip designers have started using artificial intelligence-assisted tools in their work, as opposed to more “manual” software. As a result, those designers don’t know how the products they create are actually put together.

“Increasingly, designers look at these tools and see the designs that have been generated, and say, ‘I have no idea why it generated this,’” said Dr. Aron Lindberg, an assistant professor at the School of Business at Stevens Institute of Technology. “They only know that the tool works because they can assess the quality of the finished artifact. They don’t understand why it was put together that way.”

How humans, tech relate

This work continues to build on Prof. Lindberg’s larger research themes of the relationships between humans and technology. So far, that work has encompassed areas such as the design of video games, open source software and the ways Wikipedia editors collaborate — or don’t — on the platform. He’s now eyeing generative music as a possible future thread of this research.

“I’m exploring how we relate to a world in which we have to partner with machines that do things we can’t fully understand,” Dr. Lindberg said. “Because the result has been fundamental changes in the ways that humans design and create things.”

An expert in digital innovation and design, Dr. Lindberg’s latest findings have been accepted for publication in Information Systems Research, and represent yet another avenue by which artificial intelligence is changing — not necessarily displacing — the role of humans in the workplace, as designers go from craftsmen to something more like laboratory scientists.

“THIS IS SOMETHING WE HAVE TO PREPARE STUDENTS FOR — TO WORK IN A WORLD THAT’S INCREASINGLY INFLUENCED AND DESIGNED BY THESE KINDS OF A.I. TOOLS.”

-PROF. ARON LINDBERG

“The process becomes more about experimenting with the results when they provide inputs to the tool, as opposed to understanding why the A.I. generates the results it does,” he said.

It’s a matter of technological evolution, but also necessity — as semiconductor chips have become increasingly complex, traditional software tools are having a hard time keeping up.

“This work was previously done with computer-assisted drawing software — but it was still manual,” Dr. Lindberg said. “You had designers who were knowledgeable about chips — where you would manually place wires to connect components to, for example, avoid designs that would lead to overheating — and they would place one component at a time, and build the chip from the ground up.”

Now, it’s a matter of giving the right parameters to the software and asking it to iterate on its own designs, with a designer perhaps making final tweaks at the end of the process. Designers no longer have to understand how their tools work — instead, they must be able to judge the worth of the finished product.

A shift in design work, business

This kind of seismic change has implications for the future of design work, but also in how business students are taught to engage with the world into which they graduate.

“As a technology university, Stevens has a different approach to business education,” Dr. Lindberg said. “This is something we have to prepare students for — to work in a world that’s increasingly influenced and designed by these kinds of tools.”

In one sense, those changes are already being felt in the workplace. In the past, chip design was the kind of work an electrical engineer would do, since they understand the components of a chip and how it works.

“But increasingly, companies are hiring software engineers to do this kind of work,” Dr. Lindberg said. “These engineers have a much weaker understanding of the artifact they’re designing, but a much stronger understand of these new tools used in the design. So we’re moving further away from the actual design object, and increasingly mediating that relationship with more and better software.”