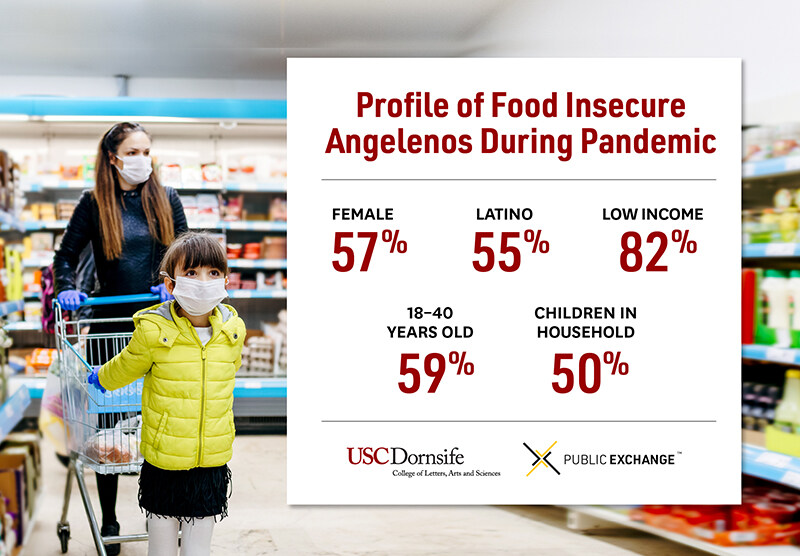

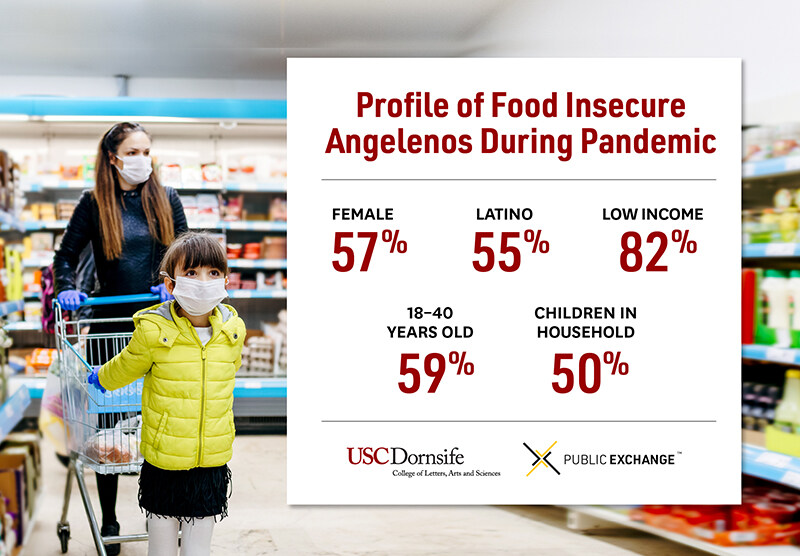

More than 1 in 4 Los Angeles County households experienced at least one instance of food insecurity – a lack of access to affordable and nutritious food – from April through July, according to a new study directed by Public Exchange, based at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. The study also found that the pandemic has overwhelmingly impacted women, people with low incomes and the unemployed, and Latinos. Higher income groups that don’t typically struggle to afford food were also affected.

Though levels of food insecurity in the county peaked in April, during the early days of the pandemic, it remains significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels.

“For the first time, we’re getting a comprehensive look at how the pandemic has impacted the ability of Los Angeles County residents to afford food,” said Kayla de la Haye, the lead researcher and assistant professor of preventive medicine at Keck School of Medicine of USC. “The spread of COVID-19 has worsened the already high levels of food insecurity among low-income households and marginalized groups and has even impacted demographic groups that are historically less likely to ever experience it.”

The study is one of the first to measure food insecurity in a major U.S. city since the start of the pandemic.

Food insecurity: Who’s impacted?

Food insecurity is a disruption in the ability to get food or to regularly eat because of limited money or other resources. Studies show that children who experience food insecurity have poorer nutrition, worse general health and oral health, and a higher risk for cognitive problems, anxiety and depression. Adults have a higher risk for obesity, diabetes and hypertension, and greater mental health and sleep problems.

During the first full months of the pandemic, April through July, 42% of low-income households in L.A. County — and 26% of all households in the county — experienced at least one instance of food insecurity. By comparison, during all 12 months of 2018, 27% of low-income households struggled with food insecurity.

The highest rate of food insecurity was in April, coinciding with L.A. County’s peak in unemployment, when nearly 40% of low-income households and a quarter of all Los Angeles households struggled at some point to afford food. By July, food insecurity rates had dropped to 14% of low-income households — still nearly triple the likely rate of July 2018 — and 10% of all L.A. County households.

“What’s particularly concerning are the 8% of residents — more than a quarter million Angelenos — who have remained food insecure throughout the pandemic,” said de la Haye. “Not only because they’re likely to be unemployed and low-income, but because they reported having fewer financial benefits and facing greater barriers to getting food, such as not having a car or a grocery store nearby.”

Nearly 1 in 5 households that experienced food insecurity during the pandemic weren’t low-income. Almost 14% had incomes between $60,000 and $100,000 per year, and nearly 6% had annual incomes of more than $100,000. Compared to 2018, many more people who experienced food insecurity were unemployed.

Pandemic’s impact on diet

The study also found that a majority of Angelenos consumed different quantities and qualities of food during the pandemic. About one-quarter said they ate more food than usual while 14% said they consumed less. And while slightly more than one-quarter said they ate healthier food –– more fruits and vegetables and less sugary and fried food –– another quarter said they ate less healthy food.

People who experienced food insecurity — particularly those who were regularly food insecure — were much more likely to experience a decline in the healthiness of their diet.

“The consequence of eating very little, other than low-cost unhealthy food, means people experiencing food insecurity are at greater risk for food-related diseases like obesity, diabetes and heart disease,” said de la Haye. This could worsen the already high rates of these diseases among the most vulnerable communities in the county.

The study was conducted in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Emergency Food Security Branch. A report of the findings has been shared with L.A. County officials.

“These research findings show just how critical it is for the county and our partners to provide food assistance and other forms of direct support to county residents during times of economic uncertainty,” said Fesia Davenport, L.A. County’s acting chief executive officer. “The county will continue expanding the important work of Let’s Feed L.A. County over the coming weeks and months in order to prevent further hunger and mitigate health impacts.”

About the Research

USC Dornsife’s Public Exchange spearheaded the study, which was conducted by researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, the USC Dornsife Spatial Sciences Institute and USC Sol Price School of Public Policy, with collaboration from the Los Angeles County Emergency Food Security Branch. It was supported by the USC Dornsife Emergency Fund, and by the Keck School of Medicine of USC COVID-19 Research Fund through a generous gift from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

The findings are from data supplied by the Understanding Coronavirus in America tracking survey, administered by the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR). The survey respondents — about 1,000 in all — are members of CESR’s Understanding America Study probability-based internet panel who participated in the tracking survey between April 1 and Aug. 4.

About Public Exchange

Based at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Public Exchange fast-tracks collaborations between academic researchers and the public and private sectors to define, analyze and solve complex problems together.