Scientists have successfully gene-engineered skin cells in the laboratory which could be used to treat a rare but sometimes debilitating genetic skin condition.

The skin disorder Epidermolysis Bullosa, or EB, is the result of a mutated gene and results in skin becoming ‘unglued’ in either the upper or lower epidermal layers so that it tears and blisters. In its severest form, the skin can blister and tear at the slightest touch, causing wounds which take a long time to heal.

This week marks International EB Awareness week and DEBRA NZ, the organisation which advocates on behalf of people with EB, is hoping to raise the profile of a condition very few people have heard of. DEBRA NZ director Anna Kemble Welch, whose son suffers from EB, says the research being done in New Zealand is very exciting.

“It is pretty much world-leading and we hope it might one day lead to effective treatment that could be life-changing for people with EB.”

Globally, EB affects around one in 50,000 people and in New Zealand, around 200 people have the condition, 20 of those with the severest form. As well as the challenges and pain of living with any type of EB, in some cases the condition affects internal mucous membranes, particularly inside the mouth and throat, and can result in early death.

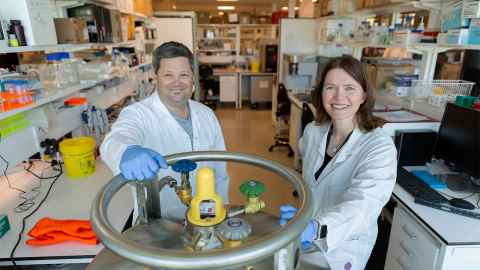

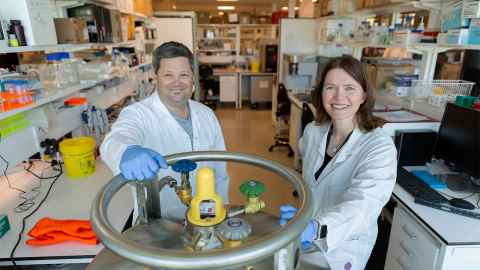

In the School of Biological Sciences Skin Lab at the University of Auckland, Drs Hilary Sheppard and Vaughan Feisst are using leading edge gene editing technology called CRISPR to generate sheets of full-thickness skin that could be used to permanently cover and/or treat chronic wounds caused by EB.

In normal skin there are about 20 genes involved in creating the cellular ‘glue’ which holds skin layers together and any of these can be mutated, leading to EB. CRISPR technology allows scientists to directly target a broken gene, a much more targeted approach in making small changes to DNA than has previously been available.

Working with colleagues at Oxford University and a team of New Zealand and international researchers, Dr Sheppard says skin is a tissue that is relatively easy to work with. Once a small biopsy has been taken, skin cells are grown in the lab and CRISPR is used to ‘fix’ the mutated, or broken, gene.

Work has been successful in editing skin cells taken from the first patient and the team are about to begin working with skin from another three patients.

“Each patient has a slightly different mutation, the one we are working with currently has a mutation in the collagen 7 gene which affects the “Velcro” or connective tissue within the layers of the skin,” she says.

“But we also want to try and edit cells from patients with other forms of EB that have the mutation in other proteins in cells that are involved in producing adhesive for skin.”

Dr Sheppard says work over the past 16 months has shown the team can achieve clinically useful levels of gene editing, a technique that might eventually be used for other conditions.

“Gene mutations are involved in a range of rare diseases which could potentially be targeted by using CRISPR. By creating patient-specific genome-edited skin we can also think about treating a wider range of skin problems such as burns.”

And it’s not only humans who suffer from EB, baby southern white rhino Zhara who was born at Hamilton Zoo this year, was born with the condition.

Both Dr Sheppard and Dr Feisst acknowledge that gene editing is a powerful tool that needs to be fully discussed and debated, not just among scientists but by the public generally.

“We are really keen to see those discussions go ahead and to see the issues, including ethical issues, fully discussed and debated. It’s important that the public understand both the potential of gene editing but also how powerful it is, so that communities have a real say in decision-making.”