A team of scientists led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has developed a device that can deliver electrical signals to and from plants, opening the door to new technologies that make use of plants.

The NTU team developed their plant ‘communication’ device by attaching a conformable electrode (a piece of conductive material) on the surface of a Venus flytrap plant using a soft and sticky adhesive known as hydrogel. With the electrode attached to the surface of the flytrap, researchers can achieve two things: pick up electrical signals to monitor how the plant responds to its environment, and transmit electrical signals to the plant, to cause it to close its leaves.

Scientists have known for decades that plants emit electrical signals to sense and respond to their environment. The NTU research team believe that developing the ability to measure the electrical signals of plants could create opportunities for a range of useful applications, such as plant-based robots that can help to pick up fragile objects, or to help enhance food security by detecting diseases in crops early.

However, plants’ electrical signals are very weak, and can only be detected when the electrode makes good contact with plant surfaces. The hairy, waxy, and irregular surfaces of plants make it difficult for any thin-film electronic device to attach and achieve reliable signal transmission.

To overcome this challenge, the NTU team drew inspiration from the electrocardiogram (ECG), which is used to detect heart abnormalities by measuring the electrical activity generated by the organ.

Transmitting electrical signals to create an on demand plant-based robot

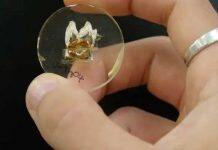

As a proof-of concept, the scientists took their plant ‘communication’ device and attached it to the surface of a Venus flytrap – a carnivorous plant with hairy leaf-lobes that close over insects when triggered.

The device has a diameter of 3 mm and is harmless to the plant. It does not affect the plant’s ability to perform photosynthesis while successfully detecting electrical signals from the plant. Using a smartphone to transmit electric pulses to the device at a specific frequency, the team elicited the Venus flytrap to close its leaves on demand, in 1.3 seconds.

The researchers have also attached the Venus flytrap to a robotic arm and, through the smartphone and the ‘communication’ device, stimulated its leaf to close and pick up a piece of wire half a millimetre in diameter.

Their findings, published in the scientific journal Nature Electronics in January, demonstrate the prospects for the future design of plant-based technological systems, say the research team. Their approach could lead to the creation of more sensitive robot grippers to pick up fragile objects that may be harmed by current rigid ones.

Picking up electrical signals to monitor crop health monitoring

The research team envisions a future where farmers can take preventive steps to protect their crops, using the plant ‘communication’ device they have developed.

Lead author of the study, Chen Xiaodong, President’s Chair Professor in Materials Science and Engineering at NTU Singapore said: “Climate change is threatening food security around the world. By monitoring the plants’ electrical signals, we may be able to detect possible distress signals and abnormalities. When used for agriculture purpose, farmers may find out when a disease is in progress, even before full‑blown symptoms appear on the crops, such as yellowed leaves. This may provide us the opportunity to act quickly to maximise crop yield for the population.”

Prof Chen, who is also Director of the Innovative Centre for Flexible Devices (iFLEX) at NTU, added that the development of the ‘communication’ device for plants monitoring exemplifies the NTU Smart Campus vision which aims to develop technologically advanced solutions for a sustainable future.

Next generation improvement: Liquid glue with stronger adhesive strength

Seeking to improve the performance of their plant ‘communication’ device, the NTU scientists also collaborated with researchers at the Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (IMRE), a unit of Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR).

Results from this separate study, published in the scientific journal Advanced Materials in March, found that by using a type of hydrogel called thermogel – which gradually transforms from liquid to a stretchable gel at room temperature – it is possible to attach their plant ‘communication’ device to a greater variety of plants (with various surface textures) and achieve higher quality signal detection, despite plants moving and growing in response to the environment.

Elaborating on this study, co-lead author Professor Chen Xiaodong said, “The thermogel-based material behaves like water in its liquid state, meaning that the adhesive layer can conform to the shape of the plant before it turns into a gel. When tested on hairy stems of the sunflower for example, this improved version of the plant ‘communication’ device achieved four to five times the adhesive strength of common hydrogel and recorded significantly stronger signals and less background noise.”

Co-lead author of the Advanced Materials study and Executive Director of IMRE, Professor Loh Xian Jun, said: “The device can now stick to more types of plant surfaces, and more securely so, marking an important step forward in the field of plant electrophysiology. It opens up new opportunities for plant-based technologies.”

Moving forward, the NTU team is looking to devise other applications using the improved version of their plant ‘communication’ device.