Residents of the Nunavut hamlet of Clyde River and the nearby communities have long known about a naturally occurring hydrocarbon seep in Baffin Bay’s Scott Inlet. For many scientists, the Arctic waters represent a unique opportunity to discover more about natural oil and gas seepage into this little-explored part of the planet.

The seep was first mentioned in mainstream scientific literature in the 1970s by the Geological Survey of Canada, with their researchers also completing a dive in 1985 to confirm the seep’s existence. Faculty of Science research assistant Margaret Cramm partnered with researchers from the federal government, Memorial University of Newfoundland, University of British Columbia (UBC), Université Laval, and the Government of Nunavut to characterize marine microbial communities around the seep. This study, recently published in Science of the Total Environment, is the first to closely examine the biology surrounding the seep.

Cramm, now a PhD student at Queen Mary University of London, first began fieldwork in the area in 2018 as a research assistant in the Geomicrobiology Group. Cramm met Dr. Bárbara de Moura Neves, PhD, a research scientist with the federal government’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada aboard the CCGS Amundsen, a research icebreaker operated by the Canadian Coast Guard. The two found that their research goals aligned, and began a close collaboration.

Queen Mary University of London; ResearchGate

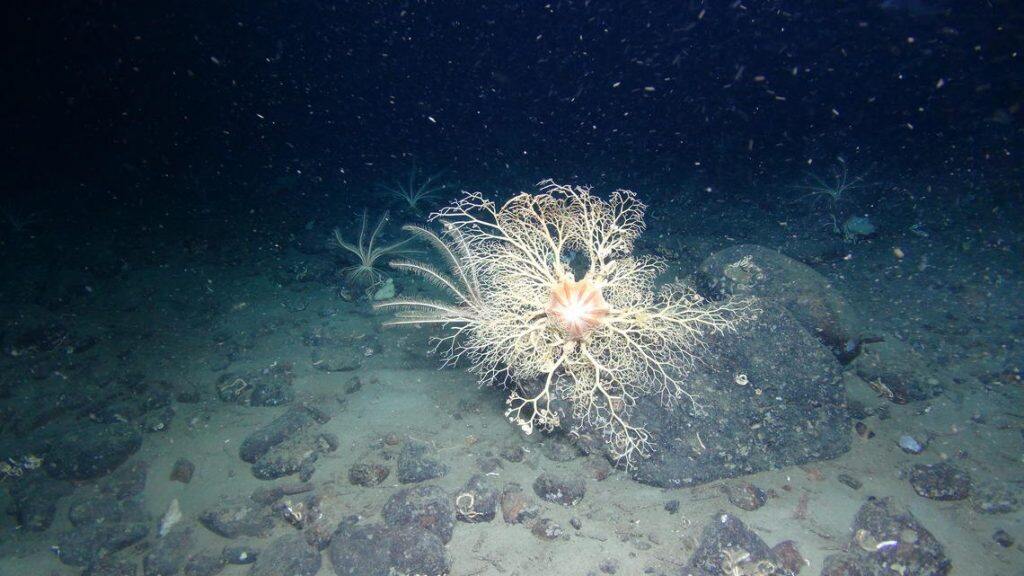

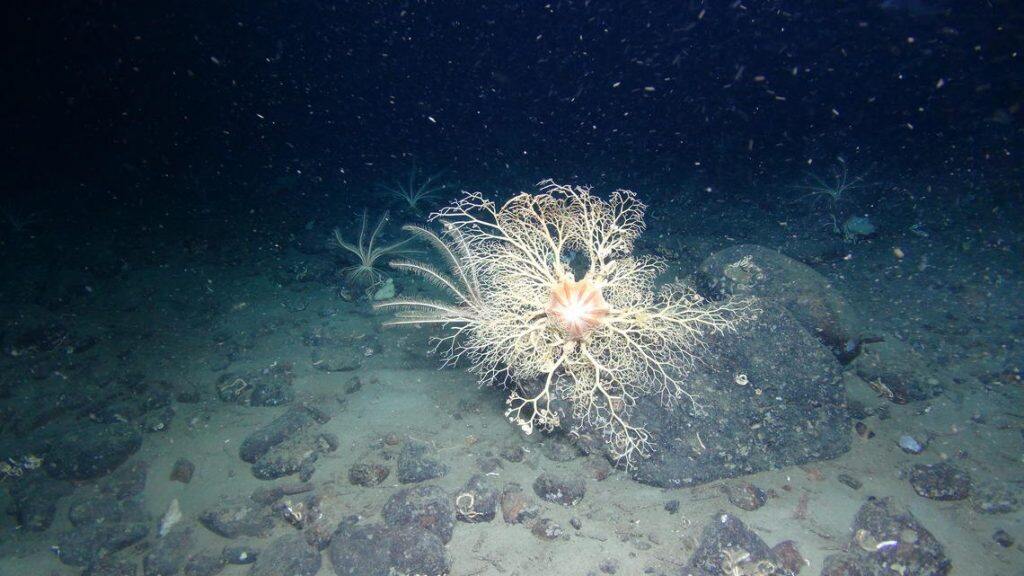

With a primary focus on exploratory research, the team used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to look at the microbiology as well as other larger organisms and animals around the seep. In addition to sediments, they sampled water from the seafloor all the way to the top of the water column.

“The seep itself has been known about and explored for a while, but using an ROV we are able to see the seafloor directly to understand how the seep affects the biology of the area,” Cramm says.

Natural environment in balance near naturally occurring seep

Underwater hydrocarbon seeps, also known as cold seeps, can, and do, occur naturally all over the world. These underwater seeps release fluids like oil and natural gas from the deep subsurface into our oceans. The hydrocarbon-rich environment created by cold seeps can be an oasis providing food for seafloor animals, particularly in deep water where food sources are sometimes limited.

Interestingly, hydrocarbon-degrading microbes can form the base of the food web at seeps, a role normally filled by photosynthetic organisms in other environments. Accordingly, using PCR-based methods, Cramm discovered populations of methane-degrading bacteria around the seep. Neves examined the animals on the sea floor.

The Arctic is a unique environment for methane-degrading microbe activity, as the microbes are often thought to be less active and slower growing in cold temperatures. The hydrocarbon seep is allowing the natural enrichment of methane-degrading bacteria in an Arctic site.

“We found that the microbial communities are in balance around the seep,” Cramm says. “The seep is giving those naturally occurring microbes that can degrade oil and gas — or methane — an opportunity to grow and be dispersed out from that area. That means that these organisms could be beneficial to the area because they’re degrading the oil and gas that comes out of that seep.”

Water samples were taken from the bottom of the ocean to the top above the seep. Cramm’s collaborators at UBC found that the methane entering the seawater at the bottom was not present in the water samples taken from the top of the water column. “This means that all the methane is being oxidized in the water column, and this methane isn’t a source of greenhouse gas entering the atmosphere,” Cramm says.

The research also found that the animals at the sea floor did not appear to be negatively affected by the seep.

“The animals seemed to be comparable near the seep as in other locations farther away,” Neves says. “We saw cold-water corals, shrimp, sea stars, some small fish, worms, sea spiders, and sponges.”

Neves, whose research focuses on cold-water corals, found high amounts of hydrocarbons in coral tissue in one sample taken from near the seep, whereas those levels were lacking in a sample taken from further away.

Next steps for the researchers, who have access to a new ROV owned by Amundsen Science (Université Laval) that can sample with more precision, is to continue their explorations to address specific questions at Scott Inlet and elsewhere.

“We’re going to a lot of places we’ve never been before, and get to see things that not many others have the opportunity to,” Neves says. “We found evidence of things we’d like to learn more about, and do more detailed research to address issues and concerns northern communities might have.

ROV photos and video footage was collected by the Canadian research icebreaker CCGS Amundsen and made available by the Amundsen Science program, which was supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.