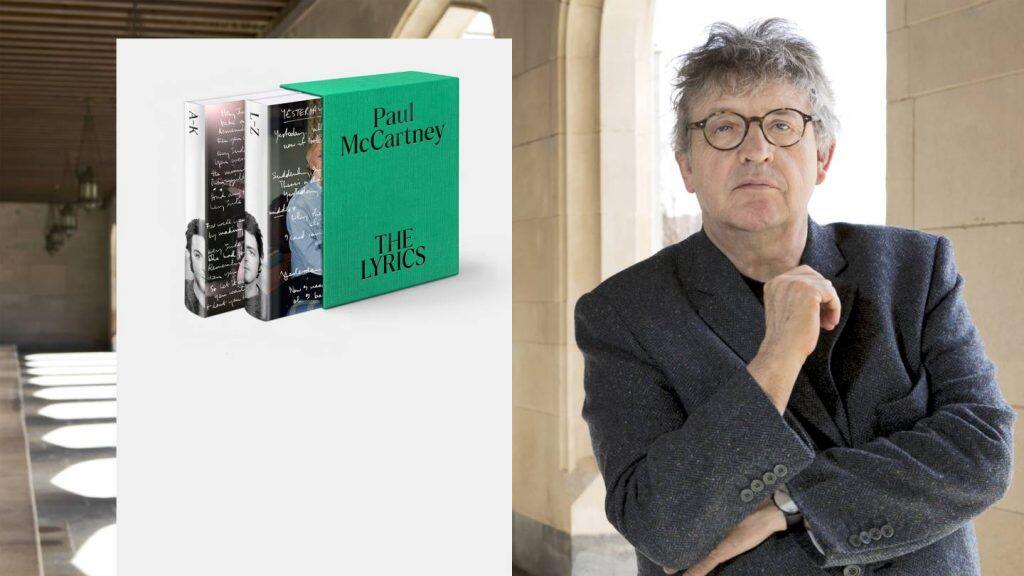

In 2015, Robert Weil, the editor-in-chief of W.W. Norton/Liveright, invited Paul Muldoon to a performance of Verdi’s “Don Carlos” at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. During each entr’acte, Weil floated the idea of Muldoon editing a book focused on the entire oeuvre of Sir Paul McCartney’s song lyrics. By the time the curtain fell on the four-and-half-hour performance, they had mapped out a plan.

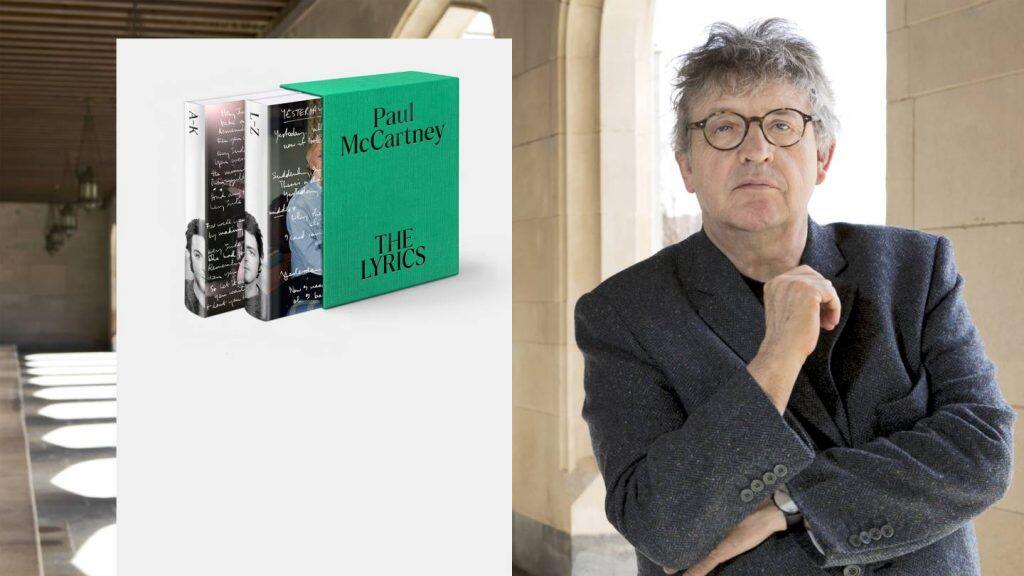

Five years and more than two dozen conversations between Muldoon and McCartney later, “The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present,” has arrived. The boxed, two-volume work illuminates the stories behind 154 of McCartney’s song lyrics — “as close to an autobiography as we may ever come,” said Muldoon, the Howard G.B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities, professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts, director of the Princeton Atelier and chair of the Fund for Irish Studies.

Muldoon, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and former poetry editor of The New Yorker, has taught poetry at Princeton since 1987 and songwriting since 2013. In February, the week before the publisher’s announcement that Muldoon was going to be the editor of “The Lyrics,” McCartney made a surprise two-hour visit via Zoom to Muldoon’s “How to Write a Song” class, in which students work in small groups to compose a song a week, each with a specific theme and focus.

Muldoon is old-school when it comes to music and still listens to CDs in his car, but he knows his way around a rock song. He once wrote the musician Warren Zevon a fan letter, which led to a collaboration on a song, “My Ride’s Here,” the title track to Zevon’s album released before his death in 2003 and later covered by Bruce Springsteen. He is the author of “The Word on the Street,” a collection of rock lyrics written for his former band the Wayside Shrines, and “Songs and Sonnets,” about the relationship between verse and song.

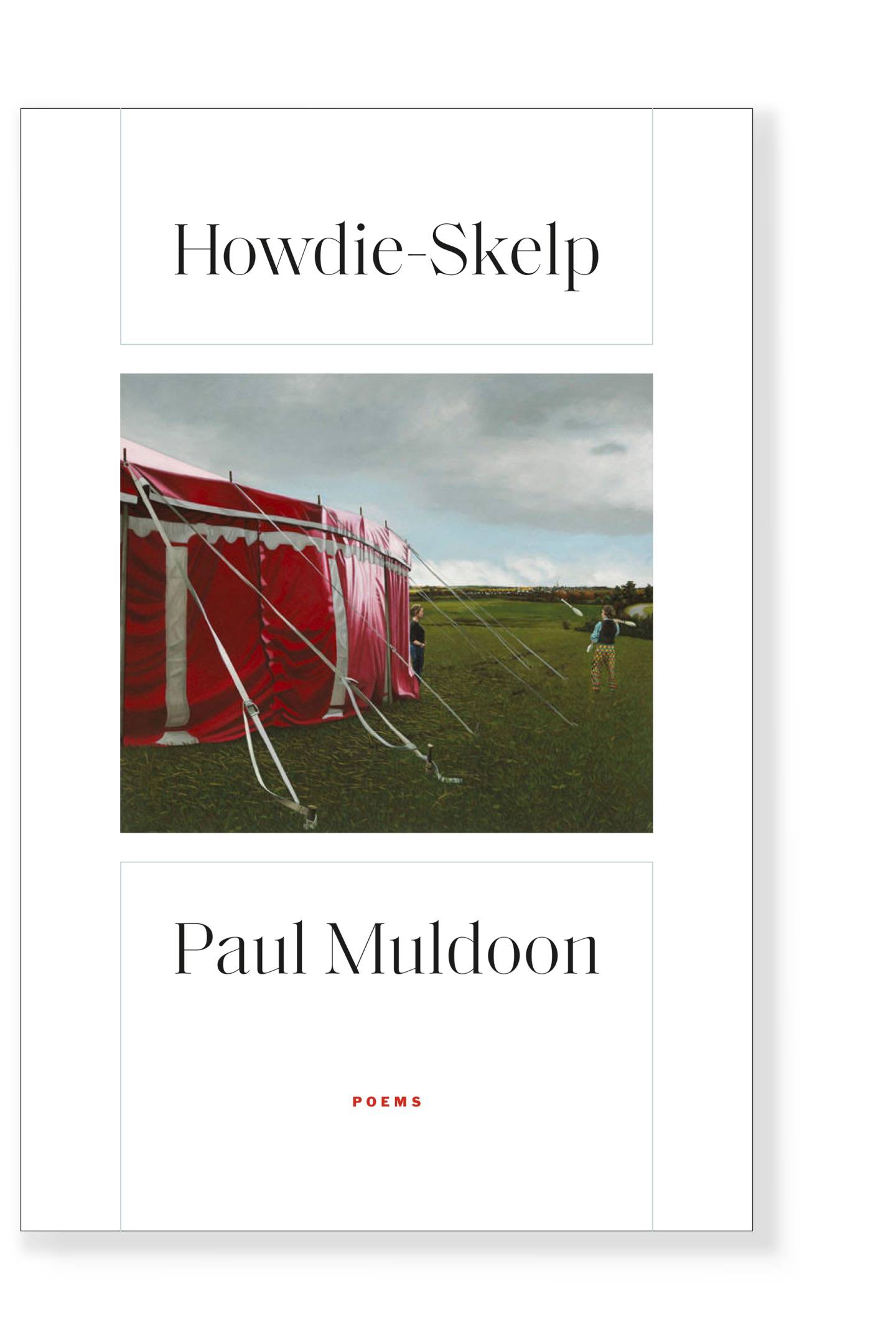

He has also written songs and spoken-word pieces for another band he is associated with, Rogue Oliphant. He is the organizer of the biennial Princeton Poetry Festival, which takes place on Nov. 12 at McCarter Theatre Center’s Berlind Theatre, showcasing poets from the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia and El Salvador. His 14th collection of poems, “Howdy-Skelp,” will be published in the U.S. by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on Nov. 16.

“The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present” is a two-volume edition in which Paul McCartney recounts his life and art through the prism of 154 songs from all stages of his career. The book is written by McCartney and is edited and introduced by Paul Muldoon, Princeton’s Howard G.B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities and a professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts. “The Lyrics” describes the songs in depth and presents contextual material such as drafts, letters and photographs from McCartney’s personal archive.Video courtesy of W.W. Norton/Liveright

Here, Muldoon reflects on the creative process he and McCartney used, Sir Paul’s knack for teaching, the joy of bringing a song into the world and the role of poetry to yank us out of our comfort zone.

The New Yorker recently published an excerpt from “The Lyrics” in which McCartney unpacks the story behind “Eleanor Rigby.” It’s a poignant, complex account with lots of moving parts. Was it easy to get McCartney to draw out these memories? Were they at his fingertips, or did they take some probing to uncover?

It might be useful to start with how the book was made. I met with Paul McCartney five or six times a year between 2015 and 2020. Our sessions usually ran for three hours and, in each, we usually discussed six or eight songs. These conversations were recorded on two machines (for safety’s sake), and then transcribed. I edited the transcription into a continuous commentary on each of 154 songs.

To answer your question, we were devoted to the idea that, somewhat like himself and John Lennon, we wouldn’t leave the room without something new to show for it. That meant that we were actually a little wary of what was at his fingertips. It was likely to give the reader a sense of déjà vu. I am very interested in the role of the unconscious in the creative process so I often tried to provoke him into ways of thinking about his songs he mightn’t otherwise have considered.

Was there a Beatles song — perhaps one of your long-time favorites — that you saw differently or felt differently about after hearing about its composition?

I felt it very important that the book be presented alphabetically rather than chronologically. One of the effects of that is, paradoxically, to underpin the continuity of Paul McCartney’s work. There’s too often a tendency to think of the Beatles era as a creative bulge — the goat in the python — while the reality is that Paul McCartney is still writing great songs. So, I found myself being surprised again and again. And I think the reader will be surprised again and again. Otherwise, there’s not a lot of point in doing the book!

You have called McCartney “a major literary figure who draws upon, and extends, the long tradition of poetry in English.” Did working so closely with him change your view of your own craft?

I found myself confirmed in my belief that poetry is a very broad church, if you’ll allow me that metaphor. A broad temple. A broad mosque. In other words, poetry comes in a huge array of guises. It certainly includes the song tradition — a fact attested by pretty much every history of poetry in English that includes “Sir Patrick Spens” or a Robin Hood ballad. It’s instructive to think of the very solid education Paul McCartney had in Liverpool. His English teacher, Alan Durband, had been a student of F.R. Leavis in Cambridge and was a major influence on Paul McCartney’s taste for what was known in the UK as Practical Criticism.

When McCartney made a surprise visit via Zoom to your “How to Write a Song” class, the theme that week was “loss” with a focus on harmony. What’s a piece of advice he gave one of the student groups that stood out to you?

One of the ideas that’s clear from “The Lyrics” is that, had he not become a Beatle, Paul McCartney would have most likely become an English teacher. His flair for teaching was certainly on display when he visited our class. There were eight groups of four songwriters presenting that day and he quite methodically gave “close readings” of the eight songs. In fact, he usually kicked off the discussion. Many of his critiques had to do with the practical rejigging of lyrics or chord structures. His most important piece of advice was that the students honor not quite knowing what they’re doing. Like many great artists, he thinks of himself primarily as a medium through which a song finds its way into the world.

You have a new book out as well, “Howdie-Skelp” (an idiom for the slap in the face a midwife gives a newborn). How is this new collection of poems — written during the COVID-19 pandemic — its own kind of “wake-up call” in the current moment?

I think of every poem as an affront of some kind. Indeed, the etymology of that word “affront” has to do with a blow to the face. Something that knocks us back on our heels. The poems I like best are at least unexpected and, more often than not, quite shocking. They force us to recalibrate. The period in which this book was written has been one in which we’ve been properly required to understand the urgency of a number of issues — racial justice, climate change, the failure of the two-party electoral system — and a number of the poems reflect those concerns. But there are also poems that are meant to have us reconsider a fly, a chipmunk, a cow moose and a bull.