The Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society has opened My Kingdom for a Title, a new solo exhibition featuring work by Pope. L, an acclaimed artist and scholar in the University of Chicago’s Department of Visual Arts.

On display through May 16, this is the first exhibition to be organized at the Neubauer Collegium gallery since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The global health crisis has unavoidably cast a shadow over the show’s conception and development; it contains allusions to the COVID crisis with a degree of directness that is unusual in Pope.L’s work, which is often elusive and ambiguous.

Although the Neubauer Collegium gallery is temporarily closed to the public in accordance with University guidelines, a virtual tour of the exhibition will be available in February.

Photo by Grant Delin

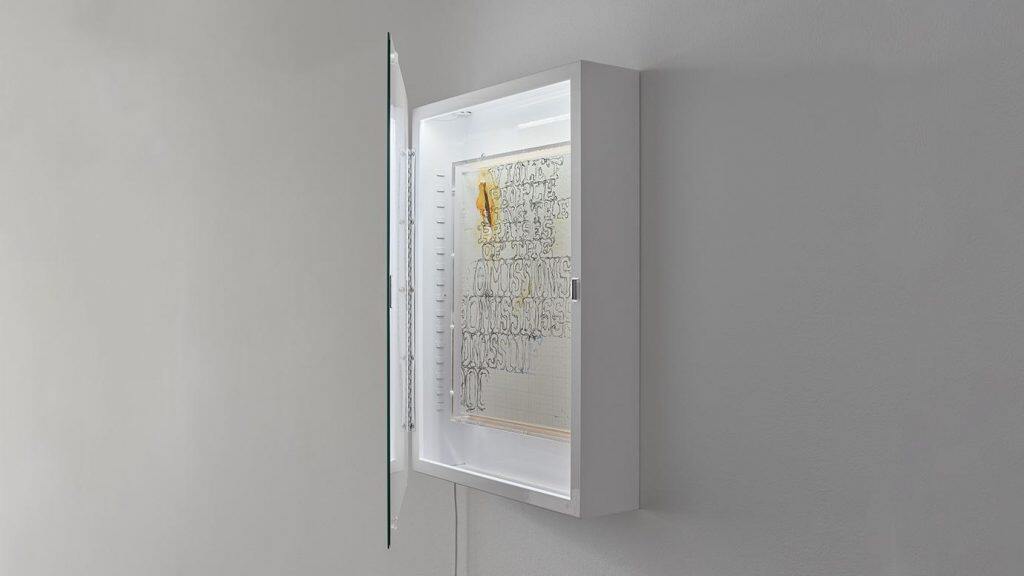

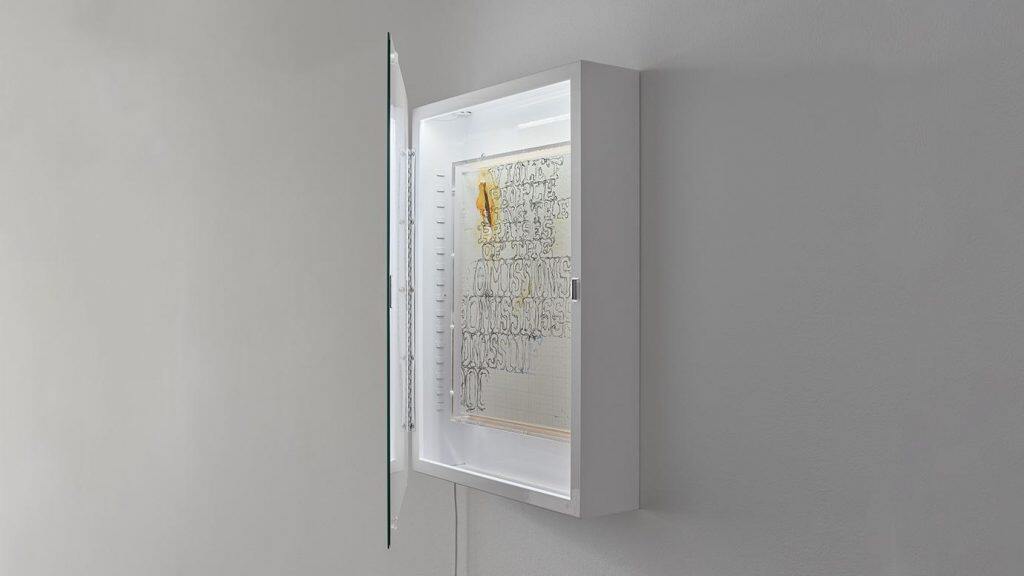

Visitors to the physical space will enter an immersive installation under a literal cloud of objects that have come to symbolize the pandemic. The centerpiece of the show is a selection of works from Pope.L’s Skin Set Project, an ongoing series of text-based drawings and paintings featuring elliptical aphorisms that call attention to the way color is deployed to categorize people. An arrangement of medicine cabinets with mirrored doors left ajar will be lit from the inside, inviting visitors to get a better look at the works contained within. The subtle play of prompts and references will animate the gallery as a space where notions of access—to art, to meaning, to health care—are entangled with those of color as conventional markers of identity.

“Pope.L is something of an escape artist for those of us who compulsively want to know what a given artwork is about,” said Neubauer Collegium curator Dieter Roelstraete, who organized the new show and has collaborated with Pope.L since 2015. “Perhaps the nature of the current moment forces us to opt for such a direct mode of address. How enigmatic can art really afford to be right now? Or should it, rather, double down on the ‘enigmaticalness’ that is the fount of so much great art?”

As an exhibition that will open without a public reception in the midst of a pandemic, My Kingdom for a Title makes a provocative case for the presentation of art as a form of essential labor. As a project revolving around the “problem” of access, the show also dramatizes the unique challenge of seeing art at a time of social distancing.

This irony is not without precedent in art history, Roelstraete said. He noted that Robert Barry’s conceptual art classic Closed Gallery (1969) consisted of a simple invitation card informing the recipients that during the exhibition, the gallery would be closed. Although My Kingdom for a Title is physically on display at the Neubauer Collegium, the lack of an in-person audience—at least for the time being—can stand as its own sort of commentary.

“Here we have a new installation by a major American artist that will be seen by far fewer people than expected or hoped for, speaking to the tragedy of so many recent losses,” Roelstraete said. “Yet through it all, art persists: ars longa, vita brevis.”

A UChicago faculty member since 2010, Pope.L has addressed similar themes in his recent interventions, staging the complex politics of racial identity, public health and access with his signature sense of the absurd. (He has referred to himself as a “fisherman of social absurdity.”) Flint Water Project, originally presented at the artist-run space What Pipeline in Detroit in 2017, featured plastic bottles filled with contaminated water from Flint, Michigan, made available as artworks for sale; all proceeds were donated to charities directly addressing the city’s water crisis. The monumental sculpture Choir (2019), on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York last winter, included a 1,000-gallon water storage tank, an upside-down water fountain (a reference, perhaps, to Jim Crow-era segregation), and copper piping that channeled the water to an inaccessible gallery on the second floor.

Pope.L first gained recognition in the 1990s with a series of arduous, provocative “crawls” in which he used his own body as material to dramatize racial and economic struggle. In the emblematic performance The Great White Way (2001–09), the artist dressed up as Superman, strapped a skateboard to his back and crawled twenty-two miles across the expanse of Manhattan’s Broadway.

Other notable performances, brought together as part of a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York last year, transformed radical protest into avant-garde theater. In Eating the Wall Street Journal (1991), the artist did exactly that, chewing and spitting out columns of financial news while seated on an American flag. For his ATM Piece (1997), he stripped down to his boots and a skirt made of dollar bills and symbolically chained himself to a bank with a string of sausages.

Roelstraete and Pope.L first worked together on The Freedom Principle (2015), a group exhibition that the former curated at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. In 2017, as a member of the curatorial team on the international contemporary art exhibition documenta 14, Roelstraete helped bring Pope.L’s works to Athens, Greece, and Kassel, Germany.

As UChicago colleagues, the pair co-taught the course “Art and Knowledge” at the Richard and Mary L. Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry in the 2018 Winter Quarter; hosted a five-hour discussion about exile and immigration as part of the Brown People Are the Wrens in the Parking Lot exhibition at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts; and published an edited volume about their collaborative efforts titled Campaign.