Downstream of hydroelectric dams and Alberta’s oil sands, one of the world’s largest freshwater deltas is drying out. New Stanford University research suggests long-term drying is making it harder for muskrats to recover from massive die-offs. It’s a sign of threats to come for many other species.

BY JOSIE GARTHWAITE

The muskrat, a stocky brown rodent the size of a Chihuahua – with a tail like a mouse, teeth like a beaver and an exceptional ability to bounce back from rapid die-offs – has lived for thousands of years in one of Earth’s largest freshwater deltas, in northeastern Alberta, Canada.

Today, this delta lies within one of the largest swaths of protected land in North America: a national park five times the size of Yellowstone that’s home to the planet’s biggest herd of free-roaming bison and the last natural nesting ground for the endangered whooping crane. It’s also central to the culture and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples, including the Mikisew Cree First Nation, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and Métis Local 125.

New research focused on muskrat population dynamics in the Peace-Athabasca Delta, published June 24 in Communications Biology, demonstrates the vulnerability of even this most protected landscape to human-driven changes to water systems and the global climate.

“A little muskrat in the middle of this northern part of Canada is an indicator of human impacts at the local, regional and global level,” said Stanford University environmental biologist Elizabeth Hadly, co-principal investigator of the study. “Climate change and dams have changed the ability of this exemplar species – and many plants, animals and people who depend on the same ecosystem – to thrive in this large area.”

The research comes on the heels of a draft finding from the United Nations that Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park – the park and World Heritage Site that contains the Peace-Athabasca Delta – is likely in danger from threats related to governance as well as hydropower and oil sands development upstream of the delta. Previous research has implicated climate change as a driver of long-term drying in the delta and hydroelectric dams on the Peace River as a cause of reduced flooding.

“Our results speak to the impacts on the biotic environment of long-term drying – whatever the cause – and this has implications for science and environmental policy,” said Stanford hydrologist Steve Gorelick, co-principal investigator of the study and a senior fellow at Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Eruption and die-off

Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) populations have always followed a boom-and-bust cycle, with their numbers crashing in dry years and peaking after major floods. But in recent decades the booms – and the area of the delta inhabited by muskrats during wet years – have been shrinking. The authors found the most recent year of net population increase after flooding, 2014, was less productive than any such growth year going back to the 1970s.

While many creatures rely on the dynamic nature of wetlands to survive, muskrats depend heavily on floodwaters, rivers and streams to travel and disperse beyond their natal ponds. “During a big flood, a lot of muskrats will drown. Some will get swept up into trees and stay put,” said lead study author Ellen Ward, who worked on the research as a PhD student in Earth system science at Stanford. “But some will stay in the water, either floating or clinging to debris, and get swept along quite far.”

As floodwaters recede, the dispersed muskrats enjoy habitat gains that support larger populations. They graze intensively on plants near the shore, strongly influencing plant life in the area and providing prey for fox, lynx, mink and other predators.

Canary in a coal mine

Because muskrat behavior and dispersal are so closely linked to freshwater distribution and abundance, their genetic data offers hard evidence for how changes in the aquatic environment have affected a real population over time. “They’re a bit of a canary in a coal mine,” said Hadly, the Paul S. and Billie Achilles Professor in Environmental Biology and a senior fellow at Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

In one flood year, DNA from a pair of closely related muskrats turned up nearly 25 miles apart, suggesting that the animals can roam or be carried far in search of suitable habitat beyond their place of birth. During dry years, the authors found population size and density decreased while the number of individuals migrating through a given location increased, suggesting overcrowding in remaining patches of habitat drives long and perilous migrations in search of viable territory.

“Our work shows they can travel great distances – far longer than their home range – and that they breed so prolifically that their population bounces back, just not to anything like it was beforehand,” said Gorelick, the Cyrus Fisher Tolman Professor in Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth).

Computer simulations and tail tissue

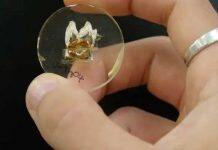

The new estimates derive from a collaborative effort combining computer simulations of freshwater habitat in the delta and muskrat behaviors, along with genetic analysis of 288 muskrat tail tissue samples collected and donated by Indigenous trappers who captured the animals for fur and meat. “Our modeling accounts for all stages of muskrat life: their travels, their diet, their reproduction and the many ways they can and do perish. They can freeze, drown, starve, be eaten or eat each other,” Gorelick said.

Both the modeling and the genetic analysis suggest muskrats in the delta today are likely grouped into many smaller populations that, taken as a whole, show a long history of rapid die-offs and what scientists call genetic bottlenecks. “Even when the population increases to the huge sizes that we see in peak years, there is not as much genetic diversity in the population as we would expect,” explained co-lead study author Katherine Solari, a postdoctoral research fellow in biology.

According to the authors, no single portion of the delta is most important for muskrat persistence. “You can’t just go to one lake and say, ‘We’re going to protect all the fish and muskrats here,’ because it will be completely different next year,” Hadly said. “It challenges us to think of how we preserve the dynamism in this landscape in the face of an altered hydrology and climate.”