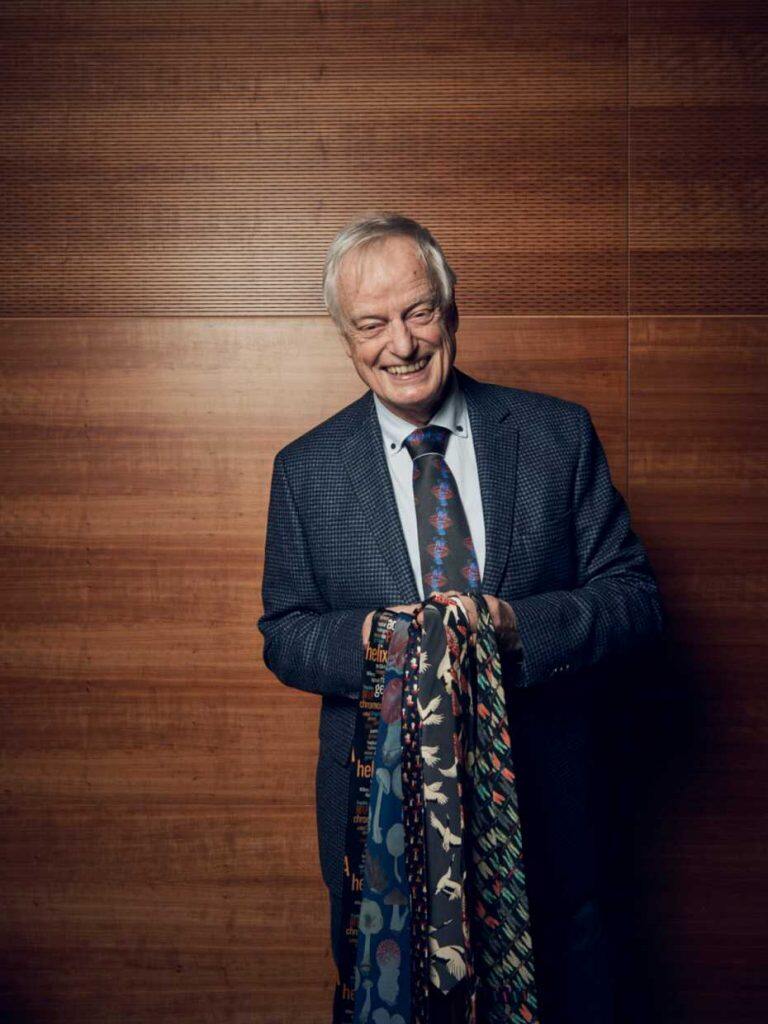

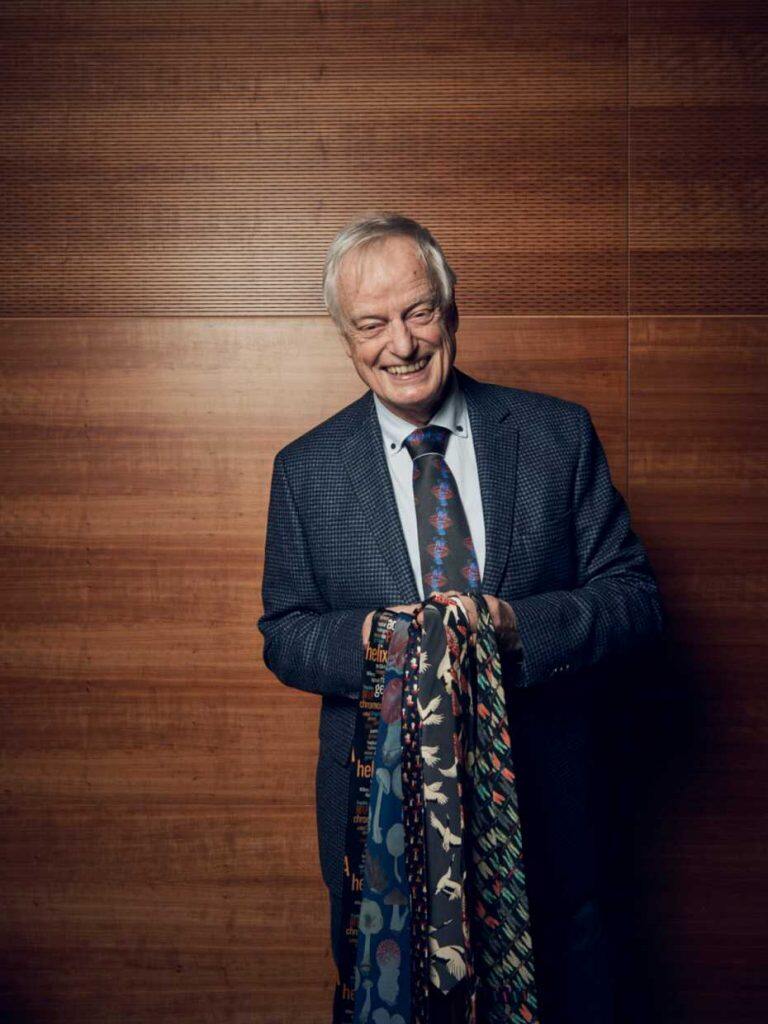

With Markus Aebi’s retirement, ETH is losing a great scientist. The microbiologist has also made a name for himself as a teacher and mentor well beyond his own discipline. His passion for research and teaching is reflected in his involvement in many university institutions – and in a series of prestigious awards.

He can barely contain his enthusiasm when looking back on his time at ETH Zurich. Even in retirement, he still feels a very strong bond with the university: “ETH provides an incredibly powerful research environment that offers so many opportunities. It’s amazing!”

The biologist was originally an undergraduate at ETH Zurich. He completed his degree and doctorate at the Institute for Microbiology. After a spell at the University of Zurich and the California Institute of Technology, he returned to Switzerland 27 years ago as professor at the Institute of Microbiology. “Such a fortuitous return is unusual in our profession. It was a unique opportunity for me.”

Aebi grabbed the chance. He quickly established himself as one of the leading global scientists in the field of glycosylation of proteins. In this biological process, proteins are refined after their synthesis with sugar molecules. Without these additives, many proteins are unfinished, because they only acquire their function through the sugar.

“I chanced upon this process as a young post-doctoral student and was fascinated by it. Mainly because it is so fundamental.” The process is extremely old in evolutionary biology terms – as old as DNA or protein synthesis itself. And it is essential for all living organisms: humans as well as bacteria.

“Initially we investigated how protein glycosylation works in bacteria and yeasts.” Eventually Aebi and his research group discovered specific mutant strains of yeast as a model for human hereditary diseases associated with congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG).

Prize-winning collaboration

Working closely with other leading European scientists, Aebi managed to identify the molecular cause of these CDGs. Their ground-breaking research was honoured with one of the highest scientific accolades in German-speaking countries: Aebi and his colleagues were awarded the Körber Prize, worth 750,000 euros, in 2004. The award ceremony in Hamburg was a highlight in the Swiss scientist’s career. “The former German President Richard von Weizsäcker gave a speech, I’ll never forgot that. It was wonderful to meet him in person.”

In the same year members of Aebi’s research group created a new spin-off, GlycoVaxyn. The knowledge acquired by Aebi and his team when investigating bacteria helped to produce a biotechnological application, in turn leading to the production of vaccines. In 2015 the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline bought the spin-off for 190 million US dollars. Today several products are already undergoing clinical trials. A glowing success story – but also a principle Aebi feels strongly about. “If it’s possible to give something back to society then it’s important to do so. With basic research, the key question is always: How does something function? As soon as we know the answer, we must make the relevant knowledge available. As scientists, I believe we have an obligation to do so.” Aebi is delighted that ETH offers such comprehensive support for knowledge transfer.

Assisted by his know-how and insight into vaccine production, Aebi’s team has recently worked with his colleague Emma Wetter Slack on the development of a coronavirus vaccine. “I’m only involved on the periphery where the content is concerned – I leave that job to the young researchers. I made available the necessary technical resources and facilities: this type of support is more appropriate for someone in the twilight of their career.”

Even though his work as an active researcher is now over, his fascination for biology is as strong as ever. Partly because biology is frequently at the interface with other disciplines. “Many biological problems need input from other disciplines to find a solution. Only now, towards the end of my active career, have I discovered productive interactions with engineering, for example. Using engineers’ methods to analyse biological systems: that’s extremely exciting.” Aebi has always been open to new approaches. Whenever he came across something that might be useful for his research, he immediately established a partnership. “And this in turn produced something new. That was great fun.”

A strong bond with students

During his time as a professor at ETH, providing support for young scientists has always been close to Aebi’s heart. “Looking after the undergraduates, graduates and doctoral students has always been personally important to me.” He particularly enjoyed giving lectures to first-year students, as he likes to engage with young people and hear their personal expectations and goals, as well as their concerns. And it always reminded him that he once sat in the very same lecture halls, but as part of the audience. “I was a disruptive student. I used to complain if the lectures were poor. When I came back later as a professor, I said to myself: “So now you can show exactly how to deliver a good lecture.”

It was a learning process, but one with a successful outcome. Students recognised the quality of his teaching with a series of prizes such as the CS Teaching Award and the ETH Golden Owl awards. “It’s rewarding when students appreciate your teaching and think you’ve done a good job.”

The appreciation is mutual: Aebi is equally inspired by his students. He is full of praise for the Swiss education system and its output of top-class high-school graduates. And he is enthused by all the young people, doctoral students and postdocs from across the globe who work in his laboratory. “People from many different cultures work together productively at ETH. Being part of such a team has been a fantastic experience.”

Many diverse interests and activities

His enthusiasm for teaching and research is also reflected in his involvement in the university’s institutions: head of the Institute for Microbiology, in charge of the degree programme in biology, head of the Biology Department, Director of Life Science Zurich, member of the ETH Research Commission, delegate to the President for the appointment of professors, to name just some of the positions he has held. “The opportunities and possibilities available at ETH are excellent. It’s been a pleasure for me to play my part in preserving the overall integrity of our institution. One can’t expect the university to continuously offer you something – you need to give something back as well.” And that’s more than just a lecture or publication.

A new chapter

During his retirement, Aebi will still be involved in the ongoing development of the ETH organisational structure as part of the rETHink project. One of his tasks is to help redevelop the professorships. “I feel very honoured that my opinion counts.” At the same time, however, he stresses the importance not just of many years of experience, but also the fresh approach of young colleagues.

He has given up all his other roles, his laboratory is being cleared out, and other lecturers are at the podium in the lecture halls. Aebi is finally leaving the main stage. “Naturally I’m still interested in science, but I no longer feel the need to practise it myself. I am delighted when something new comes up, but it doesn’t have to come from me. And I still feel young enough to take on new challenges.”

In a way, the pandemic lockdown has been a test run period for his retirement. For decades, the family father and professor left home in the mornings to work in Zurich and was often away for several days at scientific conferences. “Until now I never realised what it’s like to be at home all the time.” The test run has been successful. His wife is now closing her medical practice and retiring as well. “We are really looking forward to starting a new chapter in our lives.”