The University of Toronto has partnered with Markham, Ont.-based Edesa Biotech on laboratory studies of a drug that physicians are already using at Canadian hospitals in a clinical trial for some of their sickest patients.

Researchers at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine are about to receive their first shipment of the drug, a therapeutic antibody called EB05 that preclinical studies have shown can limit the inflammatory immune response that leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome – the main cause of death in people with COVID-19.

The researchers will study cells and animal models in the faculty’s Combined Containment Level 3 Unit (C-CL3) to see whether a molecular receptor called TLR4 plays a direct role in the overactive immune response – a condition known as a cytokine storm – and how EB05 can block the receptor and inhibit the inflammatory pathway.

“The hope is that with data from laboratory and clinical studies together, we’ll have a detailed and high-level understanding of how this therapy works to limit or prevent acute respiratory distress,” said Scott Gray-Owen, director of the C-CL3 unit and a professor of molecular genetics in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

The lab work will run in parallel with Edesa Biotech’s clinical trial, a phase 2 study with over two dozen active sites in Canada and other countries. That trial should continue into phase 3 if clinical data remain positive, helping to ease the pressure on intensive care units across the country.

Several of U of T’s partner hospitals are about to enrol their first patients in the trial, including Toronto General Hospital at University Health Network.

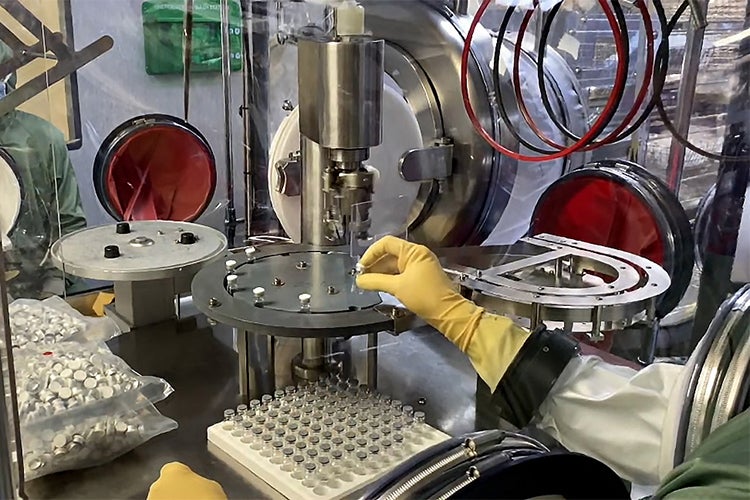

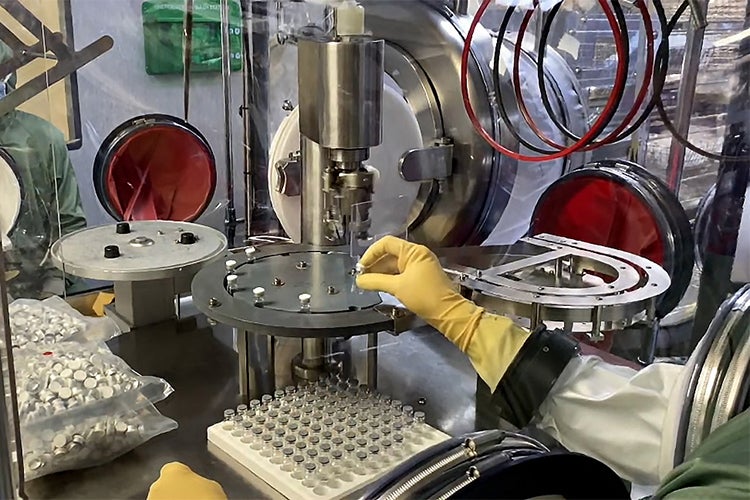

(photo courtesy of Edesa Biotech)

The federal government recently committed $14 million to help fund the trial, but federal regulators will need more clinical data before approving the new treatment for widespread use at the end of phase 3.

Gray-Owen said researchers in the C-CL3 lab aim to produce that data, and that part of the federal funding will support their work. He said the project has great promise due to its potential for immediate clinical impact, but also because the science behind the treatment is solid.

“There has been good work suggesting that targeting TLR4 could be an effective strategy, first in bacterial endotoxins and later for viruses that trigger inflammation,” Gray-Owen said. “It’s also a bit fortuitous that we’ve had two decades to figure that out, since this work highlights that the immune system is much more sophisticated than anyone first imagined.”

The path from discovery of TLR4 to treatment with a monoclonal antibody shows that the outputs of basic research are often completely unforeseen, Gray-Owen added.

Scientists identified TLR4 in the late 1990s and found that it recognizes harmful bacteria as part of the innate immune response, with two of the researchers winning the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery in 2011.

But it turns out the receptor can also detect danger signals in other cells activated by the immune system to cause inflammation as part of the adaptive immune response. Researchers now generally accept that modulating TLR4 is a valid way to up- or down-regulate immune-based inflammation.

Gray-Owen said Michael Brooks, the president of Edesa Biotech who earned his PhD in molecular genetics at U of T, understood the evolving science around TLR4 from his time in graduate school and had the foresight to see its value in emerging respiratory illnesses.

“One key to Mike’s success is that he has found opportunities where the science makes sense but is complex,” Gray-Owen said. “It can be easier in business to tell a simple and engaging story, but sometimes the explanation can be difficult.”

He said Brooks’s ability to dig into basic science and a focus on real-world applications have also been critical.

Brooks, meanwhile, credits a strong team at Edesa, many of whom are U of T graduates, for working tirelessly on the project.

“Together with the university, local hospitals and the support of the federal government, we hope this project will offer a real solution for Canadians,” said Brooks, who was one of Gray-Owen’s first graduate students and credits him for guidance on how to move from academia to industry at a time when few formal programs existed to help make the transition.

After his post-doctoral research at U of T, Brooks received a Science to Business Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to support an MBA at the Rotman School of Management. He worked in business development at Cipher Pharmaceuticals prior to joining Edesa in 2015.

Brooks said he harboured a strong interest in infectious diseases from his time at U of T, which is serendipitously coming to fruition now.

“The pandemic has really highlighted the lack of therapies for hospitalized patients with acute respiratory illnesses,” Brooks said. “We’re part of a huge drive to meet this need in industry. A therapy for COVID-19 that reduces mortality would make a big difference for patients, and for ICU capacity.”

Edesa has enrolled over half of the roughly 300 people who will be part of the EB05 trial, and staff are keenly waiting on interim data that should show how well the therapy works and in which patients.

Blair Gordon, Edesa’s vice president of research and development, completed a PhD in molecular genetics at U of T with a focus on tuberculosis under the supervision of Professor Jun Liu.

Gordon said that EB05 shows promise in COVID-19, but also for other conditions that cause respiratory distress. That includes seasonal influenza, which kills thousands of Canadians every year.

Edesa’s future lab work with researchers at U of T will look at whether EB05 is effective against the flu, as well other pathogens that originate in animals and also variants of SARS-CoV-2, said Gordon, who re-connected with Brooks shortly after graduation in a chance meeting at Toronto Pearson International Airport and later joined him at Cipher Pharmaceuticals.

Gordon said that he and Brooks share an ongoing and profound concern about the threat of infectious diseases.

“It’s become very clear that respiratory illnesses are not going away, and that they can be really devastating to us and our way of life when we aren’t prepared,” Gordon said. “So part of this work with U of T is about looking ahead to the next outbreak or zoonotic event – because it’s not about if, but when.”