A study by an international team of scientists has shed new light on the origins of a bright patch of gamma radiation toward the centre of our Milky Way.

The findings revealed the gamma-ray signal is actually coming from rapidly spinning stars belonging to a neighbouring galaxy, rather than being an indicator of dark matter.

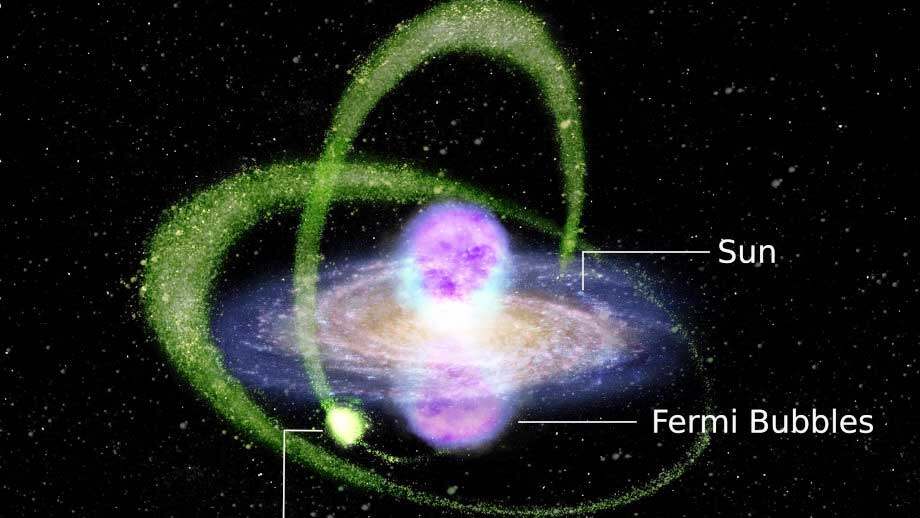

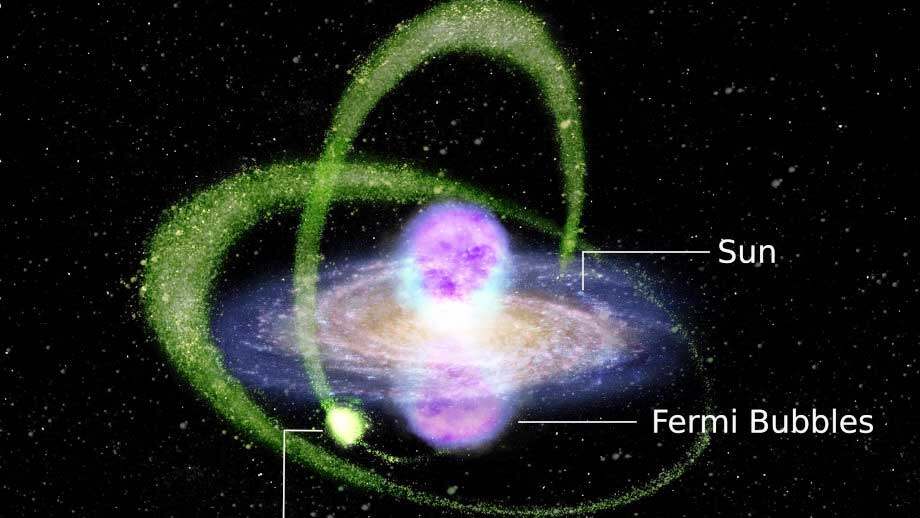

The study focused on the so-called Fermi bubbles, two globe-shaped structures spanning a whopping 50,000 light-years that were initially discovered in 2010 thanks to data collected by the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

Co-author of the study, Associate Professor Roland Crocker from The Australian National University (ANU) said that within these mysterious Fermi bubbles, there are regions which are particularly bright.

“One of the brightest spots, the Fermi cocoon, is found in the southern bubble,” Associate Professor Crocker said.

“This particularly bright patch was originally thought to be the result of a past outburst from the Galaxy’s supermassive black hole, but our study shows it’s actually coming from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy.

“This is a galaxy that actually orbits the Milky Way and which, by chance, we view through the Fermi Bubbles from the Earth’s position. The fact that the Fermi cocoon overlaps the Fermi Bubbles is essentially a coincidence.”

The Sagittarius dwarf galaxy has lost most of its interstellar gas and many of its stars have been ripped from its core thanks to the strong gravity of the Milky Way. It has no stellar nurseries – areas where gas and dust contract to form new stars.

This means its gamma radiation can only be explained by a population of millisecond pulsars – rapidly spinning neutron stars – or dark matter particles destructively colliding.

“We’ve demonstrated this emission from the Sagittarius dwarf can be explained by millisecond pulsars. The dark matter hypothesis is much less likely,” Associate Professor Crocker said.

The discovery offers new clues about the lives and habits of millisecond pulsars.

“Our findings suggest millisecond pulsars are an important source of gamma rays in inactive galaxies like Sagittarius. Similar processes could be going on in other dwarf satellite galaxies of the Milky Way,” Associate Professor Crocker said.

“This is significant because dark matter researchers have long believed an observation of gamma rays from a dwarf satellite would be a strong indicator of dark matter – this study shows otherwise, but we’re still looking for those dark matter signatures.”

The study has been published in Nature Astronomy.