People living on the ‘Swahili coast’ – the Indian Ocean coast of eastern Africa – have African and Asian ancestry according to new research on ancient DNA.

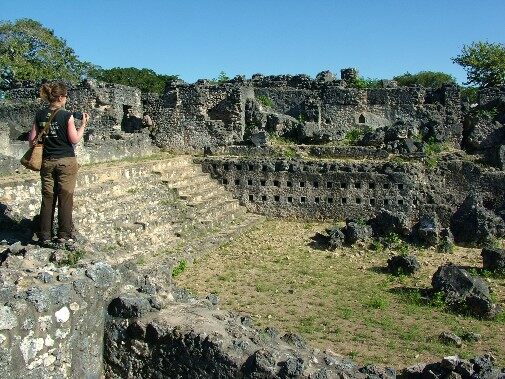

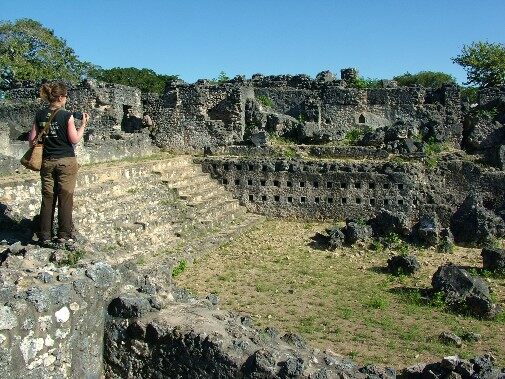

Archaeologists believe that the results, based on finds from excavations, including those directed by Professor Stephanie Wynne-Jones from the University of York and Professor Jeffrey Fleisher at Rice University, confirm that relationships between Asian merchants and African traders were formed between the years 900 and 1100 in coastal towns in Kenya and Tanzania.

DNA analysis, conducted at the Reich Laboratory at Harvard University, allowed scientists to estimate that people of African and Persian descent began to have children together around the turn of the second millennium. The descendants of those children dominated Swahili towns 500 years later and were recovered from the burial sites excavated by the team.

Genetic timeframe

Professor Stephanie Wynne-Jones, co-author of the study from the University of York’s Department of Archaeology, said: “We have long believed that cultural changes were associated with the adoption of Islam and this new research gives us a genetic timeframe that suggests that this is a reasonable assumption to make.

“Merchants from Persia travelled to the African coast for trade, and would have stayed for long periods of time. DNA from the burial sites we have been studying shows African and Persian ancestry. The Persian line came from men, suggesting they were forming relationships with African women.”

Oral histories

Some 500 years later we see ancestry coming from Arabia rather than Persia, probably related to shifting economic and political influences.

Jeffrey Fleisher, from Rice University, and one co-author of the study, said: “Oral histories of the Swahili who live in East Africa have often told us of their Persian ancestry, which for many years researchers have believed was a way for the Swahili people to use their Persian and other foreign trade links for political gain, but our data reveals that these oral records were correct, showing how important it is to take oral traditions seriously.”

The study, published in the journal Nature, has shed new light on Swahili culture, long associated with archaeological research suggesting African ancestry for all coastal civilisations.

Deep connections

Professor Wynne-Jones said: “This data must be seen as a catalyst for a new, less binary, approach to Swahili society. It shows that people were moving and establishing deep connections and families in the Indian Ocean region, and that Persian migrants would have been part of the cosmopolitan world created by coastal African societies.

“The research that has underpinned this study is part of a long-term commitment to exploring human experience and daily life on the coast.”