A team of archaeologists, co-led by a researcher at the University of Southampton, believe they have located the site of the lost Monastery of Deer in Northeast Scotland.

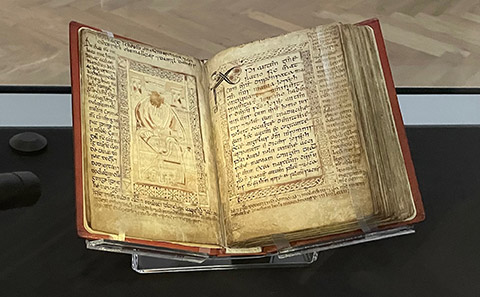

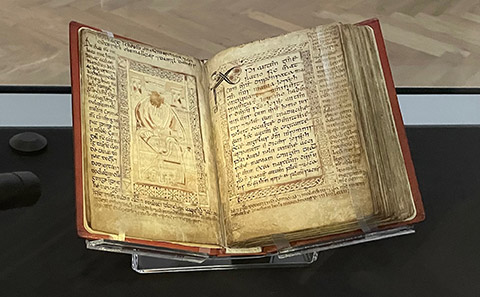

It is believed that the earliest written Scots Gaelic in the world was produced in the monastery in the late 11th and early 12th century. These texts, Gaelic land grants, were placed in the margins of the Book of Deer, a pocket gospel book, originally written between 850AD and 1000AD.

Academics have long speculated that these entries, or ‘addenda’ were added while the book was in the monastery. Archaeologists believe they have now found the building’s remains, just 80 metres from the ruins of Deer Abbey (founded in 1219), close to the village of Mintlaw in Aberdeenshire.

Alice Jaspars, PhD researcher from the Archaeology department at the University of Southampton, c0-led the archaeological investigations, working with Site Director Ali Cameron of Cameron Archaeology. They will present their findings in a lecture to the Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (23 November) and also feature in a new documentary about the project for BBC Alba (20 November, 9pm).

Alice Jaspars comments: “As home to the earliest surviving Scots Gaelic, the Book of Deer is a vital manuscript in Scottish history. While it is not known where the book itself was written, it is believed that the Gaelic in its margins was added in the formerly lost Monastery of Deer.

“These addenda include reference to the foundation of the monastery, alongside other land grants in the Northeast of Scotland. It is now our belief that in our 2022 excavation, we found the lost monastery where these were written. This would not have been possible without the extensive work of our volunteers, and the financial backing of the National Lottery Heritage Fund.”

The team carbon-dated material associated with post holes they uncovered during excavations close to the abbey, which match the same time period as the addenda in the book. They also meticulously recovered medieval pottery, fragments of glass, a stylus (pointed writing implement) and hnefatafl boards – a chess-like game that was popular until the middle ages. These and other domestic artefacts recovered at the site all point towards a monastery complex.

Investigations, supported by the Book of Deer Project, have been ongoing since 2009, with several significant excavations taking place over the last eight years. The last of these was in 2022, concentrated close to the abbey ruins and funded largely by a National Lottery Heritage Fund grant, which Jaspars and Cameron co-investigated.

The 2022 investigations coincided with the Book of Deer returning to Northeast Scotland for the first time in a thousand years. It was displayed in Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums while on a three-month loan from Cambridge University Library.

Alice Jaspars says: “The material record of monasteries from this period is so poor that finds such as these can really help to inform our overall academic understanding. This also adds to the ongoing discussion regarding where the Book of Deer is cared for in the future.”

The researchers plan to publish their results in an academic journal in the coming months.