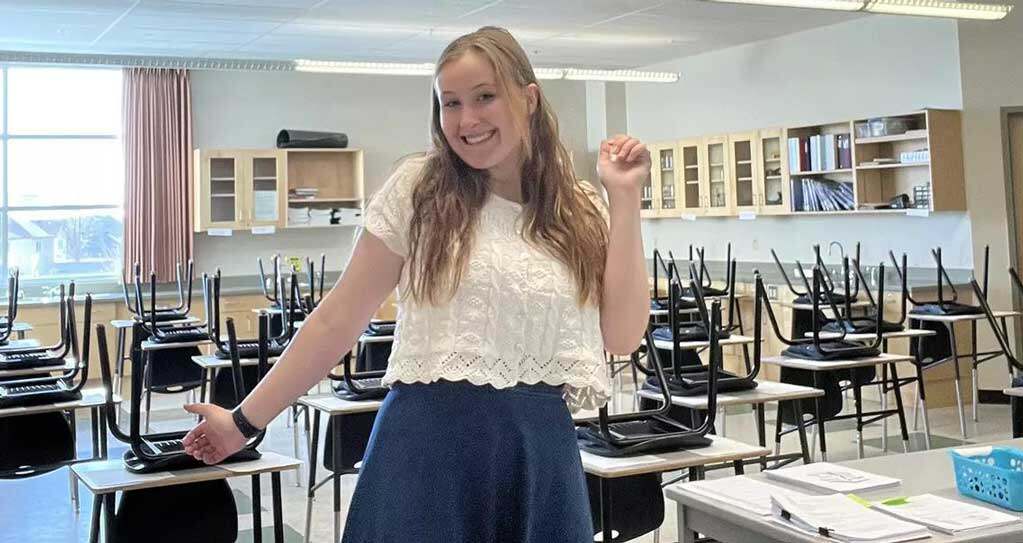

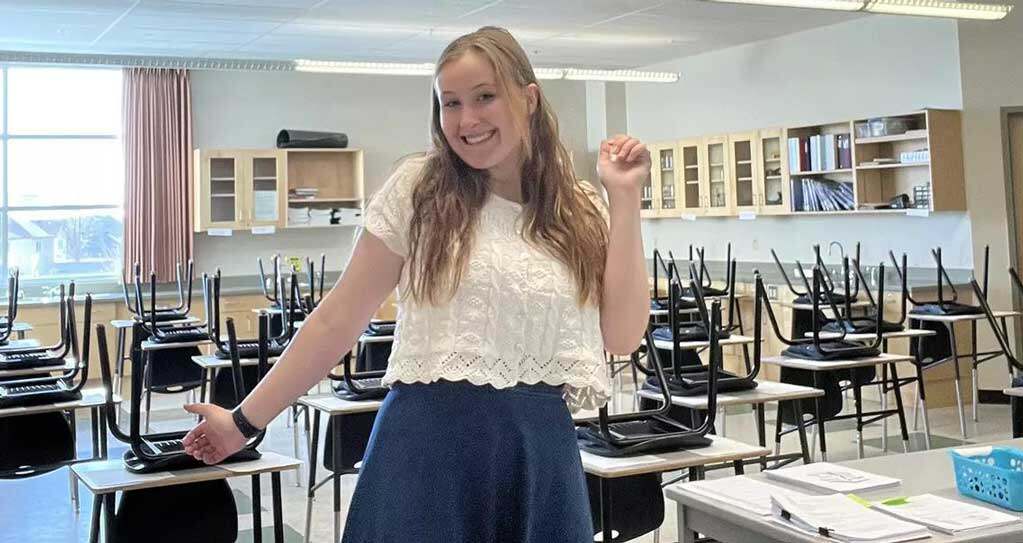

Courtesy Arianna Mamer

Arianna Mamer got bit by the science bug as a high school student in Rocky Mountain House, Alta. — something she attributes to the excellence of her teachers, particularly her physics instructor.

“I was definitely one of those students that was really afraid of physics,” says Mamer, who graduates this spring with a BSc and BEd from the University of Calgary. “Of course, my parents were like, ‘You’re taking all three sciences,’ and then physics ended up being my favourite. My high school physics teacher just made it not scary. I think that if I can pay that forward, that would be super cool for me.”

Mamer has already begun combating fear and apprehension toward science, albeit in a quite different context. In the summer of 2022, as a recipient of a PURE Award, she hosted a series of workshops on Critical Science Literacy for her peers in pre-service teaching at the Werklund School of Education.

She says seeing people become increasingly skeptical of science as the pandemic wore on served as the impetus for the project.

“We really saw that with COVID: [researchers] said one thing, but then new research came out and now we have this other thing,” she explains. “That really messed with people — no one knew what to believe.

“SO, THAT’S WHERE THIS PROJECT CAME FROM: WE NEED TO TEACH PEOPLE THAT IT’S OKAY IF SCIENCE CHANGES BECAUSE WE’RE HUMANS AND WE’RE GOING TO MAKE MISTAKES AND WE’RE GOING TO FIND NEW WAYS TO DO THINGS BECAUSE WE ARE CONSTANTLY IMPROVING.”

As an extension of Critical Theory, a social theory rooted in philosophy that attempts to interrogate, critique, and challenge power structures, Critical Science Literacy according to Mamer is a skill that “requires questioning of potential biases in the way in which science is presented to us and the consideration of socio-political implications which impact science and its use in our society.”

Which isn’t to say practising Critical Science Literacy is a means for reinforcing the status quo. Far from it. As science is no more immune to bias than any other discipline, Mamer says it’s integral to ask why certain studies are funded and who benefits from any given strand of research.

In her workshops, Mamer challenged her peers to not only interrogate concepts from multiple perspectives but to also consider ways to introduce different perspectives in the classroom.

“The purpose of my research was to look at practices that teachers can implement to get students to not blindly accept everything they’re told,” she says. “Honestly, it is just really emphasizing questioning. If they ask you a question, answer them with a question. The thing I found through this research was to just ask kids questions, because this leads to inquiry-based learning.”

Now that this stage of her formal education draws to a close, Mamer says she’s looking forward to her own inquiry-based job research through subbing. Though she initially envisioned herself as a Physics 30 teacher, her field placement experience at St. Elizabeth Seton Junior High in northwest Calgary and a subsequent contract at another junior high this spring have found her re-evaluating her own assumptions.

“Middle school was awesome. I could see myself teaching junior high, which is not what I expected. Everyone around me is like, ‘Junior high, are you sure?’ I don’t know… those kids are maniacs, but I love them,” she says with a laugh.

“Honestly, I’m happy to just sub for a bit and really get experience with different age groups.”