June is Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Pride Month, which celebrates the work necessary, both past and present, to achieve justice and equality for members of the LGBT community. Professor Jennifer Ingleheart, from our Department of Classics and Ancient History, is an expert on the influence of ancient Rome on modern understandings of homosexuality.

Q: What are your primary research interests?

‘Platonic’ love, lesbian Sappho, the Sacred Band of Thebes and its army of lovers who fought nobly alongside their beloved, preferring death to dishonour in his eyes. These are just some of the stereotypes and myths that have circulated about ancient Greece, which early activists for homosexual rights took as the model of a society in which same-sex love was widely accepted and even celebrated. My own research has focused on modern responses to ancient Rome, a culture which has received far less attention in the history of sexuality but has been just as important. In the apologetic writings of pioneering campaigners such as John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) and Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), Rome is demonised as having corrupted Greek homosexuality through its luxury, obscenity, and licence. Such heavily polarised approaches to ancient Greece and Rome were used to create a politically acceptable, desexualised version of modern homosexuality as sanctioned by the respectable example of Greece.

I’m interested in exploring the less well-known story of Rome’s impact on modern ideas about sexuality, and in particular, in modern authors who have taken a very different approach from authors such as Symonds and Carpenter, and have chosen to embrace Roman ‘degeneracy’ or ‘decadence’. My research has therefore often focused on texts with an explicitly pornographic agenda.

Q: What queer possibilities can antiquity offer to the modern day?

My research on modern responses to ancient Roman sexuality has shown that it is precisely Rome’s queerness that makes it attractive to some. Many pornographic responses to Rome celebrate elements that deviate from contemporary mainstream morals — its licence, and the sense that, sexually, many options are possible. I’d argue that Rome is more relevant than Greece to queer people today precisely because it appears franker and more open about sex, and offers us broader and more varied possibilities relating to sexuality, sex, and gender.

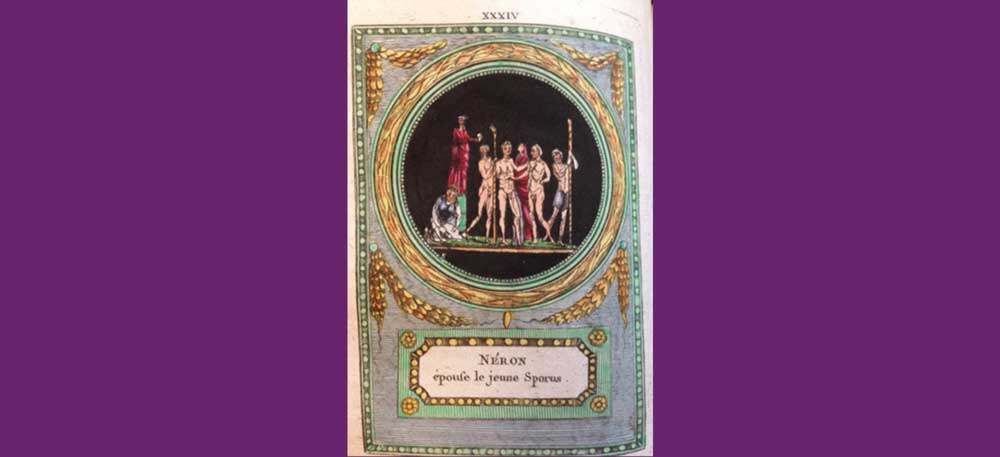

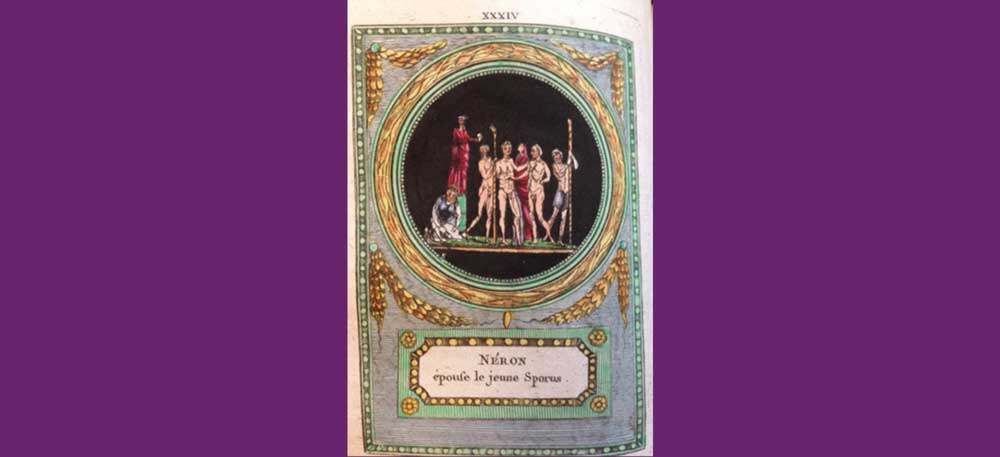

Rome abounds in queer possibilities – just one example can be found in hostile accounts of emperors such as Nero, who offended against contemporary gender norms by same-sex weddings to two separate men: in one wedding, he maintained the ‘masculine’ role that was expected of Roman men by acting as the groom, but in the other, scandalously, he played the role of the bride, expressing his pleasure on his wedding night at being ‘deflowered’ by his well-endowed partner. Rome doesn’t offer us a conforming, assimilationist model for gay marriage that suggests queer people are, or want to be, just like heterosexuals — rather, it holds out the more radical possibilities of queer role-playing, sexual versatility, and the deliberate subversion of the institution and norms of marriage.

Q: Why is exploring historical queerness so important for queer people living today?

In modern societies which take a negative view of queerness and attempt to suppress it, the very idea that there have been other times and cultures in which queerness has been possible is hugely powerful. This operates on an individual, personal level, in addition to the broader political uses to which such precedents have been put.

Classics occupies a less central place in society today than in the world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when classically educated men (for the most part) found in antiquity a rare space in which homosexuality was even a possible topic for discussion, as well as understanding and acceptance of their homosexuality. In the present day in many countries, there is widespread public acceptance of a range of queer identities and of same-sex relationships and there are plenty of other positive and more recent role models available for queer people. And yet, ancient Greece and Rome continue to matter to LGBTQ+ people because they provide us with examples of our queer ancestors – it remains immensely important to many of us be able to look back thousands of years and find traces of our forerunners in the past. Historical examples of queerness also continue to offer an important counternarrative to claims that, for example, queer or trans identities are a modern fad.

Q: One of your interests has been censorship of queer communities. In the context of Pride Month, in which queer people are encouraged to be open and proud about their identities, can you explain the importance of this research?

Many of the texts that my research has focused on have fallen victim to censorship, either because they have pornographic content or simply because their treatment of homosexuality was deemed unpalatable – and this includes even works which are highly negative about Roman sexuality. My research has explored ‘underground’ writings that are relatively well known, including the Victorian pornographic novel Teleny, sometimes attributed to Oscar Wilde, and less well-known works that circulated only in very limited editions, such as a Latin dialogue which presents a sex scene between two public schoolboys, written by Philip Gillespie Bainbrigge (1890-1918). Censorship is not ‘just’ a historical phenomenon for members of the LGBTQ+ community – currently, many schools and libraries in the United States are banning books because of their queer content, with the stated aim of protecting young people. But those who grow up as LGBTQ+ continue to be harmed by the notion that the very fact of their non-normative sexuality and/or gender is taboo, and by having their access restricted to materials that reflect their own lived experience or desires.