In 2010, the American billionaire and philanthropist Julian Robertson established a set of postdoctoral fellowships for exceptional early career researchers at the University of Auckland.

The goal of the fellowships, now numbering 22, was to “preserve the University’s leading-edge medical research capabilities and the resulting benefits to society through the development of new treatments”.

The fellowships were exceptional: they were financially generous and, perhaps most importantly, were awarded for a minimum of three years. For researchers working in academia, the postdoctoral years are the most uncertain and securing grants to undertake meaningful projects can resemble a lottery. Dr Peter Freestone was awarded one of the first neurological fellowships through the Centre for Brain Research (CBR).

“I think the time the Aotearoa Foundation Fellowship gives you can’t be underestimated,” he says. “In a worst case one-year grant, almost before you’ve begun the project you are starting the lengthy process of looking and applying for the next grant. That three years was very good.”

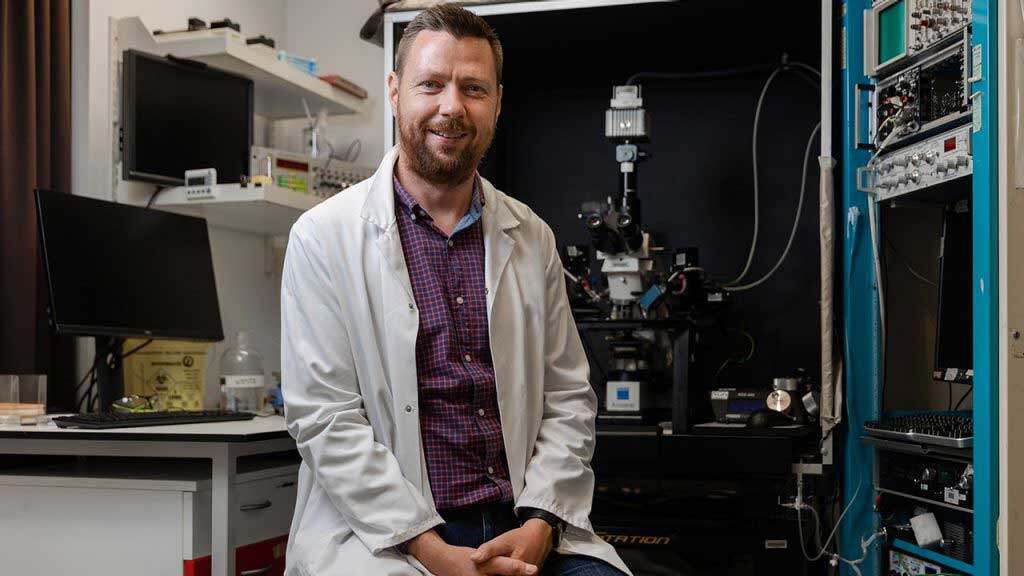

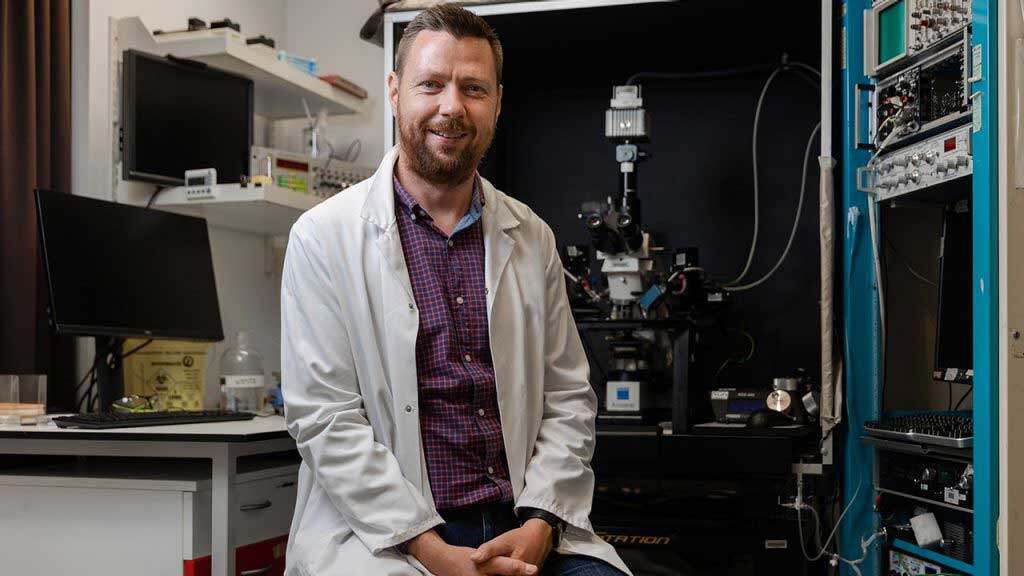

Now, ten years later, the direction of his current research in Parkinson’s disease can be traced back to projects in his original application: “It’s studying Parkinson’s disease, it’s using cutting-edge technologies to study brain networks affected by the disease, always with the aim of looking for and identifying possible new treatment strategies.”

Julian Robertson once asked him if he had cured Parkinson’s disease. “I had to sorely disappoint him but assure him I was still working on it!”

For Australian-born exercise scientist Dr Sian Williams, who took up her fellowship at the Liggins Institute in 2021, the impact was immediate.

“To be blunt, I probably wouldn’t be in New Zealand without it,” she says. The grant that supported her role in a Centre for Research Excellence project in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences was coming to an end. Her area of research has always been in cerebral palsy, especially with children and rehabilitation. Over time she moved to working with younger and younger children until she “accidentally fell into the area of early diagnosis of cerebral palsy”. The Liggins Institute fellowship opened the door to tracing the early developmentof babies born with a high risk of cerebral palsy as well as a broader and largely overlooked group of babies born moderate-to-late preterm.

Dr Soroush Safaei, a principal scientist at the Auckland Bioengineering Institute (ABI) and founder of the Virtual Brain Project, is equally direct. When asked whether he would be in the position he is now without his fellowship, he replies, “Absolutely not. That would have been impossible because the one thing we don’t have in academia is job security and funding security. This fellowship gave me peace of mind for four years.” During that time, he built the foundation for a brain research group, something the Institute’s director, Distinguished Professor Peter Hunter, had always wanted.

In a research organisation known worldwide for its modelling of the organs of the human body, the brain was the only organ without a dedicated research group. Soroush and his colleague Dr Gonzo Maso Talou now lead a 15-strong team recruited over the past four years.

One of the primary goals of the fellowships’ founder, the late Julian Robertson, was that the science should benefit society. Each of the researchers talks of that connection, its influence and importance.

“It’s really easy as a researcher to become siloed,” Sian says. “You read all the articles and look at the numbers but none of that means anything unless it’s meaningful to the person you’re doing the research for. It’s really important for us to involve people with lived experiences at all stages of our research.”

She talks of a project she co-designed where families with a child recently diagnosed with cerebral palsy and the clinicians involved talk together through the trauma of that emotionally tough time.

“It really helped guide where we went next.” Another study, which looks at the growth of muscle and function across the first year of life in babies born preterm, full term and those with a high risk of cerebral palsy, has never been done before.

“We don’t even know what normal muscle growth and the relationship with motor development looks like in typical babies, let alone babies born preterm. And I know why now,” she adds laughing. “It’s difficult to do.”

She is also collaborating with scientists at ABI and CBR on different ways of analysing muscle movement in children with cerebral palsy and how to automate the process. Instead of spending hours looking at videos of hundreds of babies, a video could be loaded into a computer programmed to detect a risk of cerebral palsy. The potential for earlier diagnosis is huge and the impact worldwide.

Peter Freestone’s research has always been based broadly on Parkinson’s disease. He admits his initial attraction was love of science and discovery, of questions we don’t have the answers to and where, with the right preparation, you can design an experiment to try to find an answer.

But as he learnt more of Parkinson’s disease there were added attractions. “There’s nothing for sharpening the mind like speaking to a room full of people who are suffering from the disease you are trying hard to cure or alleviate.” The other is a more personal journey – a close family friend who has the disease, seeing them and their family struggle with it and the desperation to try almost anything.

Then late last year he met with colleagues who have identified a very rare form of Parkinson’s disease. “Genetic causes of Parkinson’s disease contribute only a very few cases globally. This is a real anomaly. There’s a gene mutation that leads to a great number of cases in the Pacific population, and it is early onset so it’s even more devastating. They live with the disease far longer.” The game plan now is to find money to begin experiments to understand this singular form.

For Soroush Safaei, his focus on Alzheimer’s disease is a very personal story. He was at high school in Iran when his grandmother developed Alzheimer’s. Soroush followed her progress to the end, 15 long years. Most of the research was from one angle almost exclusively – clumps of the protein amyloid beta in the brain tissue – and in two decades there were no breakthroughs. However, Soroush, along with a few other researchers, have been taking a different approach, looking into the role of blood flow and hypertension.

Modelling the brain was a way to start putting together the pieces of a very complex problem to see if he could predict which part of the brain is being affected and when. The virtual brain now has a role in a three-year clinical study in collaboration with Mātai, the new not-for-profit research MRI centre in Gisborne. Starting in 2023, they will monitor changes in 50 people with symptoms of early-stage dementia. The study is another outcome of his Aotearoa Fellowship.

So too are new opportunities. He has been offered a contract in Europe with one of the largest pharmaceutical companies working in oncology.

“When I presented what I did in the past four years in building a new research group, they were amazed. They said, just come here and start working for us.” He smiles broadly. “There’s a lot to weigh up but I will come back to ABI. I’m not going to lose this connection.”

It would seem Julian Robertson’s ambitions for the fellowships – to keep research at the University operating at the highest level and contributing to improved health in society – is being realised not just in New Zealand but internationally.

Julian was a generous donor and friend to the University and a wonderful champion for New Zealand globally. Over many years, Julian’s generosity supported exciting new research into some of the most complex medical and technological challenges.

Julian Robertson, KNZM, died in August 2022. In 2009 he was awarded New Zealand’s first honorary knighthood for services to business and philanthropy. The University of Auckland awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in Law in 2018.