When NASA visited recently, it said New Zealand was well-placed to play a role in ‘the golden age of space exploration’. But how sustainable and future-proof is space technology?

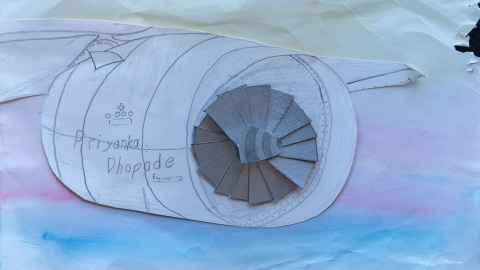

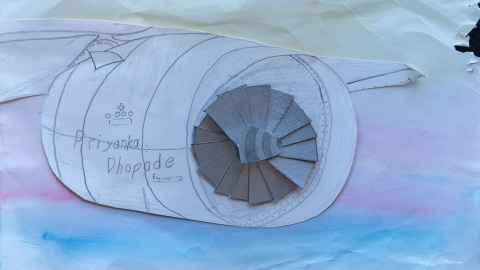

Dr Priyanka Dhopade had always dreamed of being an astronaut when she was growing up.

“For as long as I can remember, I was looking up at the sky and wondering what’s out there,” she says.

Priyanka was born in India and spent her early childhood in Saudi Arabia. She was ten when her family moved to Canada.

At school one day, there was a talk by Roberta Bondar, the first Canadian woman to travel to space.

“I remember thinking, ‘I want to do something like that,’” she says.

In 2016, she got her chance when she tried out to be an astronaut for the Canadian space programme. Out of 3,700 people that applied, she made it to the top 72 candidates.

The opportunity was “a dream come true,” she says. “But it was always going to be a long shot.”

Unfortunately it wasn’t to be, but she had a backup plan anyway. After completing her PhD in aerospace engineering at UNSW Canberra, she took a senior research position at the University of Oxford and, in 2017, was named as one of the Top 50 Women in Engineering Under 35 by the Women’s Engineering Society in the UK.

The role at Oxford had an aviation focus and involved working with Rolls-Royce Holdings to design cooling systems for aircraft jet engines. But she always wanted to get back to working in the space sector.

“Both my husband and I are aerospace engineers, and we were keeping an eye on what’s happening around the world. The emerging space sector in New Zealand is an exciting place to be because there’s so much happening. So we thought, ‘Why not have an adventure and try something new.’”

“HOW AM I ADDING VALUE? HOW AM I GOING TO LEAVE A LEGACY THAT HAS IMPROVED THE ENVIRONMENT AROUND ME?“

-Dr Priyanka Dhopade, aerospace engineerMechanical and Mechatronics Engineering, University of Auckland

She began working in the Faculty of Engineering in 2020, and is a lecturer in thermofluids in Mechanical Engineering.

She is also investigating the environmental impact of space activity with a transdisciplinary team of researchers from across the University.

The space sector in New Zealand is soaring, with a report commissioned by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment in 2019 estimating it’s worth $1.75 billion.

With New Zealand’s commitment to a net-zero carbon future, Priyanka says we need to look beyond economic measures of success and think about the potential consequences of such a fast-growing industry.

“We’ve become increasingly reliant on space technology, whether it’s for telecommunications, GPS, or internet access. Satellite data is used to inform things like environmental policy, stock investment choices and geopolitical decisions, yet there’s no public information on the trade-off between what we’re sending up to space and the actual value it’s adding,” she says.

As one of the few space-faring nations in the world with launch capability, New Zealand could choose to do things differently, says Priyanka. The team are using systems-thinking to understand how sustainable and future-proof our space technology really is and plan to use the data to create design practices that help to reduce the industry’s carbon footprint.

“WE’VE BECOME RELIANT ON SPACE TECHNOLOGY, WHETHER IT’S FOR TELECOMMUNICATIONS, GPS, OR INTERNET ACCESS … YET THERE’S NO PUBLIC INFORMATION ON THE TRADE-OFF BETWEEN WHAT WE’RE SENDING UP TO SPACE AND THE ACTUAL VALUE IT’S ADDING.“

–Dr Priyanka Dhopade, aerospace engineer, lecturerFaculty of Engineering, University of Auckland

Transdisciplinary research is a great catalyst to bring sustainable thinking to the table, says Priyanka, but it requires us to challenge our “business as usual” mindset.

“The main thing we want to achieve is more inclusivity around how decisions are made and an evidence base for some of these decisions. Some of our research shows that there are some gaps, particularly the absence of Māori leadership, and an approach led by the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

“If we don’t have the right people around the table and make room for them to challenge business-as-usual, then we’re missing out,” she says. “It’s a no-brainer, but sometimes people make it out to be more difficult than actual rocket science.”

Priyanka’s research is guided by a belief in having something to stand for and a strong value system to back it up.

“I just want to leave this place slightly better than how I found it,” she says.

“For a long time, my value system has defined everything that I do, including how I do research, how I teach and how I interact with students. All of that is around asking, ‘How am I adding value? How am I going to leave a legacy that has improved the environment around me?’”

After arriving in New Zealand, she helped to set up Women In Space Aotearoa New Zealand, a programme that provides mentorship for women and gender minorities wanting to pursue a career in the local space sector.

She knows first-hand just how overlooked and underestimated women in the industry are.

“I continue to be underestimated because I think differently, and I’m never the loudest person in the room,” she says. “I think that says more about the culture and the environment than it does about me.”

Growing up, she says her biggest role models were her parents and teachers.

“With a lot of the outreach work I’m involved in we are often asked, as women engineers, to go into schools. I can see why people think it’s a good idea. There is value in it, but I’m always the first one to say, ‘let’s talk to the parents, the grandparents, the aunts, the uncles and the teachers’, because research shows they’re the ones who influence a child’s self-perception and their career choices.”

Priyanka’s own career choices have worked out well, but she hasn’t given up her dream of being an astronaut. When asked if she would ever consider trying out again, there’s no hesitation.

“Absolutely,” she says.

Story by Hussein Moses