The University of Southampton has completed a world-first collaboration with the National Museum of the Royal Navy exploring how Artificial Intelligence (AI) can support the museum’s vital work in preserving the nation’s maritime heritage.

The project has seen three Masters students from Southampton work alongside archaeologists and curators at the museum to apply the latest AI technologies to a series of projects, including the restoration of HMS Victory – Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson’s famous flagship during the Battle of Trafalgar.

Guided by the University of Southampton’s CORMSIS research group – a collaboration between the Southampton Business School and the School of Mathematical Sciences – the project has given the students the opportunity to push AI technologies to the limit when it comes to managing and applying the huge amounts of information held by knowledge institutes.

Currently undergoing an ambitious ten-year restoration, the HMS Victory ‘Big Repair’ project involves a team of shipwrights, riggers, conservators and archaeologists who are painstakingly documenting every detail of the work. This helps to capture vital information about historical repairs to the ship, parts that have degraded and informs planning for the next stages of the work.

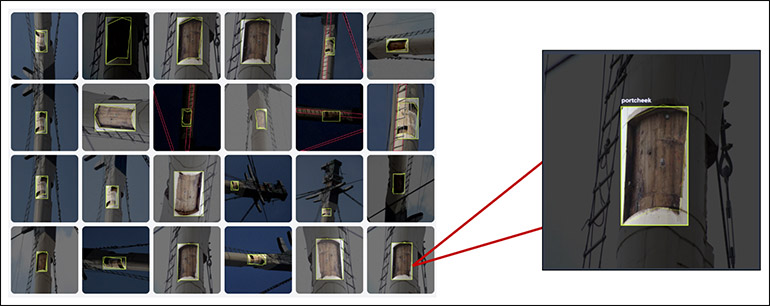

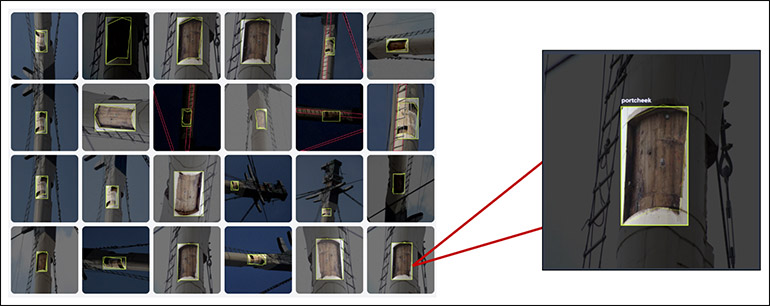

Since the restoration of HMS Victory began in May 2022, archaeologists have taken over 3,000 images in addition to the high-resolution images taken to produce multiple 3D digital models of the ship. These additional images had to be stored and analysed manually, but aided by AI, this process is now automated, increasing the quality and resolution of the recording of the works.

Dr Rodrigo Pacheco-Ruiz, Visiting Fellow in Maritime Archaeology at the University of Southampton and National Museum of the Royal Navy Archaeological Data Manager for HMS Victory, explains: “Archaeologists are obsessed with detail and if records are not accurately stored, vital historical information could be lost forever. This is where the help of our University of Southampton students has been invaluable. They have developed an AI-based algorithm to match images stored in different locations and add them to our digital 3D model to ensure it’s as accurate as possible.

“This work has pushed the boundaries of what this type of AI is capable of, as our images are extremely high resolution, complex and detailed. The project is really at the forefront of how AI is being used in archaeology – we’re demonstrating just what’s possible. It’s certainly a long way from the traditional perception of how an archaeologist spends their time.”

The collaboration also involved a project to help catalogue the museum’s collections, which include everything from figureheads, uniforms and maps to photographic, film and video material.

The way items are recorded has changed hugely for the museum sector in recent years. Where previously a curator would add a short description of an object to a physical catalogue card, they must now capture detailed information to allow for digital cataloguing and, crucially, retrieval.

Collections Information and Access Manager for the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Amy Adams, comments: “Members of the public increasingly want access digitally, so the workload of a curator in terms of capturing the necessary data has risen considerably. We still want people to visit in-person of course, but the opportunity to share knowledge worldwide and engage more and more people in our nation’s maritime history is huge.

“By working with students from the University, we were able to use AI for entity recognition – to retrieve and sort through digital records. This has huge time saving potential, but also what was really interesting was AI’s ability to label records from the perspective of a visitor, so records are categorised by what people are likely to be searching for (‘WWII ship’ for example) as well as its official name. The human touch is not obsolete, as the technology still needs that context to focus and drive it forward, but it’s certainly exciting to think of the potential AI has for the museums sector.”

Professor Bart Baesens of the University of Southampton Business School and KU Leuven University in Belgium supervised the students. Commenting on the collaboration he said: “This project has provided a fantastic experience for our students, giving them the opportunity to apply what they study to a ‘real world’ situation. They have used large language models – deep learning algorithms which can recognise, summarise and generate content – to automatically classify images and artefacts curated by the museum. We think this could be of great interest to the wider cultural world, for institutions looking to quickly, efficiently and accurately enrich the data relating to their collections.”