Floating in microgravity high above Calgary, Makenna Kuzyk saw her future flash before her eyes.

She’d wanted to be an astronaut for as long as she could remember, the kind of kid who was incapable of dreaming small. For a time, she wanted to be a famous singer, making up songs and singing them at the dinner table. Then it was a WNBA basketball player, so she shot endless hoops at the local gym.

Exploring space was the dream that stuck.

“My dad was a space enthusiast, so we’d go out and look at the stars,” says Kuzyk. “I remember seeing the International Space Station, and I said, ‘Dad, one day I’m going there.’ He was like, ‘Yep, it’s hard work, but I’m sure you will.’”

Setting a course for the stars

In her Cochrane high school, she was flipping through a recruitment magazine from the University of Alberta and came across a photo of young woman in a spacesuit.

“She’s smiling and the caption says, ‘My name is Abby — I’m in mechanical engineering at the U of A, and I want to be an astronaut,’” recalls Kuzyk.

“I just thought she was so cool.” She reached out to Abby Lacson, told her she seemed “super awesome,” and they agreed to meet. That’s when Kuzyk set her course for the stars without looking back, entering the U of A’s mechanical engineering program.

Lacson mentored Kuzyk through her first year, helping her with chemistry labs and recruiting her for AlbertaSat, a group that designed, built and launched Alberta’s first satellite and continues to build satellites to this day.

Last May, Kuzyk graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from the U of A. This Monday she was in Montreal to accept the prestigious Order of the White Rose from Polytechnique Montréal, a $50,000 memorial scholarship given each year to a Canadian female engineering student to pursue graduate studies anywhere in the world.

Now in its 10th year, the award is a tribute to the 14 young women who lost their lives in the École Polytechnique tragedy of 1989, an event that sent shock waves through Quebec and the rest of Canada.

“I feel like the award gives me a chance to keep those women’s dreams alive and work towards building a better future,” says Kuzyk. “I have pretty big ambitions, and the scholarship goes miles towards enabling me to do my master’s program.”

Career arc

In January, Kuzyk will begin her master’s degree in flight test engineering at the International Test Pilot School in London, Ont., the biggest independent school of experimental flight testing in the world. That particular dream took flight during the aforementioned “parabolic” flight above Calgary.

As an undergrad, she had started a student club called Mission Space Walker, the first all-women group in a national competition called the Canadian Reduced Gravity Experiment. The program allows post-secondary students to design and test a small scientific experiment on board the National Research Council of Canada’s Falcon 20, which has been modified for reduced-gravity flight with the help of the Canadian Space Agency.

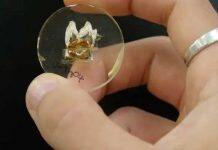

Parabolic flights provide a microgravity environment for short periods of time so researchers can conduct scientific experiments and test technologies and equipment. Kuzyk’s team designed an experiment for testing electro-adhesive robotics for space applications, such as putting these adhesive devices on a robot’s wheels.

“This basically makes the wheels ‘sticky,’ which could help robots stay attached to meteorites while conducting science, or could be applied to astronaut moon boots so they can walk on the side of the space station,” says Kuzyk.

During the reduced-gravity flight — with the first all-female team ever to compete in the competition — it dawned on Kuzyk what she wanted to do with the rest of her life.

“Floating in microgravity was crazy,” she says. “You look out the window, and it looks like the plane is angled straight towards the ground, and you’re like, Oh my gosh.

“I went straight to the test pilots and flight test engineers and said, ‘I want to work for you guys.’ Every single day that week I would be like, ‘I want to work for you guys, I want to work for you guys.’”

Now her sights are set even higher. She doesn’t want to just work for the Canadian Reduced Gravity Experiment — she wants to run the program and help Canada keep pace in the space race.

A crucial step was getting her pilot’s licence, which she completed in San Francisco just last month, soaring over the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz after saving the money to train since she was a teenager.

“I eventually want to come back to the National Research Council and run the microgravity platform and grow it, because Canada’s Falcon 20 could be retired, and that would be a big loss for Canada,” she says.

“I want to make sure the platform doesn’t die, so other people can experience microgravity. Then I’ll extend it into suborbital flights and get contracts with Virgin Galactic for commercial flights. I really think Canada has an opportunity to be part of space, and microgravity is just a stepping stone.”

Lacson now works for MDA, a defence and space manufacturing company that helps the Canadian Space Agency support International Space Station activities. She also trains astronauts on the Canadarm, which was developed by another U of A grad, Garry Lindberg.

Kuzyk is determined to follow in Lacson’s wake. It wouldn’t be a stretch to one day look up at the blinking lights in the sky and know they are both soaring through space, the best possible tribute to 14 young women who lost their lives in 1989.