A new book by Gallatin’s Eugenia Kisin examines the role of aesthetics in protest, history, and cultural resistance and preservation.

Starting in the early 19th-century, the Canadian government pursued a variety of legislative efforts to dehumanize and oppress Indigenous people, including members of Haida, Coast Salish, Kwakwaka’wakw, Gitxsan, Tsimshian, and Nisga’a Nations, whom they felt were not assimilated into Euro-Canadian culture.

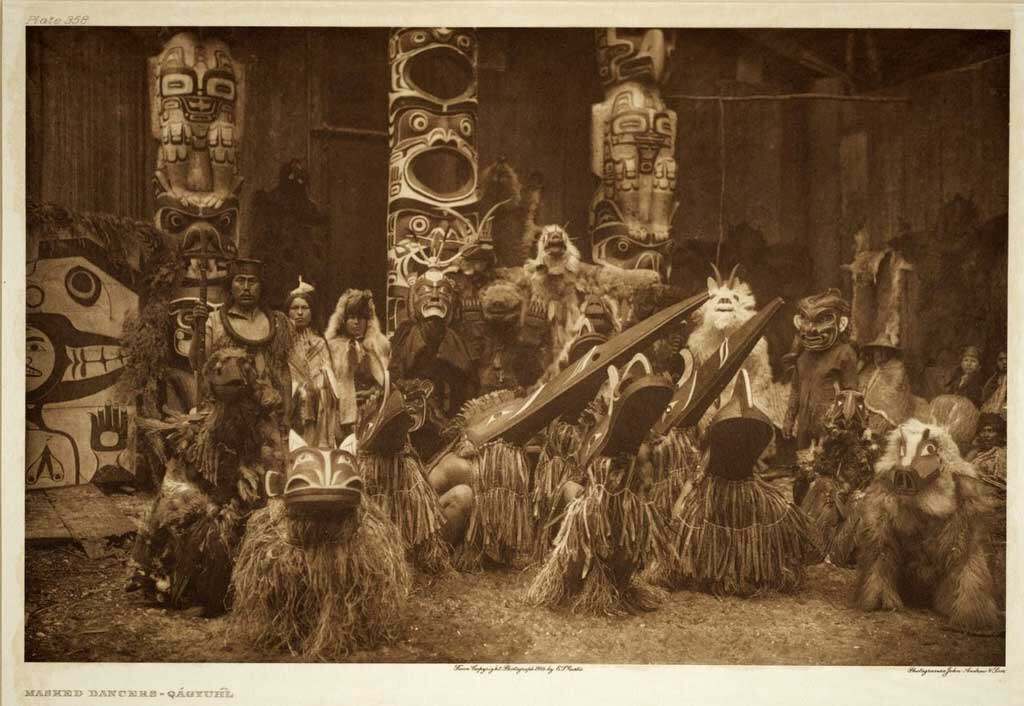

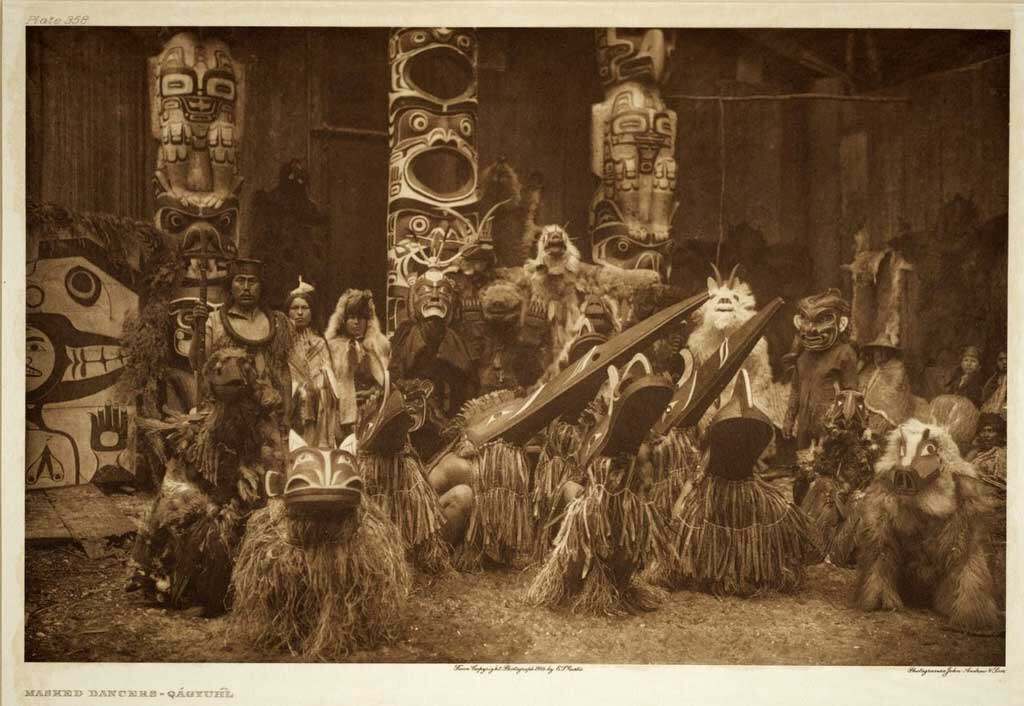

Among these efforts, the government established the Residential School system. These church- and state-run institutions were filled with Indigenous children who were taken from their homes and often subjected to physical, sexual, and mental abuse, resulting in the death of more than 3,000 children. The school system lasted more than a century and by the time the last school closed in 1996, approximately 150,000 children had been residents. In 1885, the Canadian government banned potlatches—festive and legal ceremonies held by Indigenous tribes in the Northwest Coast comprising feasts, dancing, and gifts—as a way to discourage Indigenous culture and law. And in the 21st-century, Indigenous tribes have organized and opposed the development of oil pipelines on tribal land, sometimes victorious, other times reconciling with continued development. The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which had been delayed for years and was heavily protested for expanding through tribal lands, was approved in 2024.

One common thread in all these scenarios is art—art employed as protest, history, and cultural resistance and preservation. In Aesthetics of Repair: Indigenous Art and the Form of Reconciliation, Gallatin associate professor Eugenia Kisin unpacks ways that Indigenous people in British Columbia have created and disseminated art on pressing social issues—negotiating meaning, reclaiming works of art for their communities, and reconciling conflicting feelings about government oppression, while creating art through government support.

In 2013, Kwakwaka’wakw chief and artist Beau Dick joined more than 100 Indigenous people at British Columbia’s Legislative Assembly to revive a traditional practice that had not been performed for decades. He cut a copper—a shield-like ceremonial object—on the legislative steps, a symbolic shaming ritual for the government’s exploitation of land and resources. “Bewildered media coverage fixated on what the breaking of copper means and makes tangible for Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations in Canada…but almost immediately, a parallel conversation emerged among critics, gallerists, and scholars about whether and how to claim this work as art,” Kisin writes.

NYU News spoke with Kisin about her latest work tracing the evolution of art and protest over time.

Why is British Columbia the focus of this ethnography?

I first moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, when I was 18 for university, and its visible Indigenous presence felt very different to me from other cities. There was spectacularly beautiful Northwest Coast-style carving and painting everywhere, and everyone was talking about the contemporary treaty process and Indigenous rights, particularly in relation to so-called “wars in the woods”—politics around logging, mining, and other forms of resource extraction on unceded lands and waters. Yet the public celebration of the art didn’t match up with persistent anxieties—and often overt hostility from non-Indigenous commentators—about what it might mean to actually honor treaty obligations in the present.

The second reason has to do with my interest in museums: art from the Northwest Coast has shaped Americanist anthropology, defining how we theorize gift-giving, reciprocity, cultures of display, and now, questions of restitution and return in museums, including at the Natural History Museum here in New York, which has one of the most spectacular collections of late-19th century art and cultural property from the region—a fact that should cause us to ask how and why. These things we call “art” are profoundly relational in Indigenous philosophies from this region—so much so that now, most scholars working on the Northwest Coast call these things “belongings,” following Musqueam scholar Jordan Wilson’s phrasing. These belongings, as cultural property, are also sometimes being-like in their capacities as legal entities, embodying and documenting privilege, lineage, and community status.

So I returned to British Columbia from New York to try to think about art and politics together with contemporary Indigenous artists, and in relation to form—because, as I argue in the book, form is an important source of art’s efficacy. Later in my research, as Canada carried out its Truth and Reconciliation Commission to attempt redress for the genocidal violence perpetrated against generations of Indigenous children in state and church-run Residential Schools, this efficacy became even more politically charged. In the TRC, art became a form of testimony, a unique property of this Truth Commission. I wanted to know how this was possible—indeed, why art became thinkable as testimony in this particular place and moment in time—and how it drew on Indigenous understandings of art’s capacity to mediate social relations. This is what I mean by the “aesthetics of repair”—forms that seek to remediate damage and enable a more just world.

What findings were most surprising during your research for this book?

Reconciliation, and other official attempts to repair relations between settler and Indigenous communities in Canada, have not been a resounding success. Many damaging extractive projects have proceeded on stolen land with the most minimal, disingenuous consultations with Elders and knowledge-holders; Indigenous men continue to be incarcerated at much higher rates than other citizens in Canada; and of the 94 Calls to Action that came out of the TRC’s recommendations in 2015—a wide range of reforms like improving child-welfare so that fewer Indigenous children are taken from their families, promoting Indigenous language revitalization, and making sure that public education includes curriculum on the history and impact of Residential Schools—only eleven have been fully implemented nationwide. This failure, at least on a structural level, was apparent to the artists and activists I was working with more than a decade ago. As many of them pointed out, Reconciliation was dead almost the moment it arrived.

And yet there is also repair, a less state-led, more everyday process of reconciliation with a small “r,” which I observed happening in museums, art schools, and public spaces. And these everyday practices of reconciliation mostly had nothing to do with Indigenous people “reconciling” with non-Indigenous people or institutions. This was most apparent to me in my time at the Freda Diesing School, an Indigenous-run art school in the northern part of British Columbia, where students of mixed Indigenous backgrounds learn to build their careers and reconnect to their communities through art practice and language study. I had come to Freda Diesing to co-teach an art history course with one of my collaborators, the Haida/Nisga’a artist Luke Parnell, but what I came away with was a sense of the deep reparative work that was going on at the school. For example, the school had recently carved a totem pole in solidarity with Indigenous survivors of the devastating 2008 earthquake in China, extending diplomacy and exchange relations across the Pacific. During my stay, First Nations school officials were working with a Native American foundation to develop indicators of successful grant administration that valued the school’s cultural effects—things like a sense of pride, ability to fulfill ceremonial obligations, and likeliness of returning to contribute to the curriculum. As I argue in the book, these actions are also processes of repair, and helped me see others that were happening around art, quietly adjacent to the processes of state Reconciliation.

What frustrations were most often expressed by Indigenous artists whose work was supported by government funding?

Most funding for the arts in Canada is supported by the government, and, like any centralized system, it is full of the usual bureaucratic headaches, jealousy and competition, and opacity that contributes to suspicion about how decisions are actually made—all the problems of humans applying for limited funding in a small pool. But for Indigenous artists, the categories for these funds, in the terminology used in the time of my research, the categories of “Aboriginal art,” generated specific frustrations. As one Haida artist explained to me, she did not want to apply to the Aboriginal-specific art competitions because she felt it forced her to reduce the meaning of her work to “Indigenous themes”—a tokenizing gesture that she worried would shape and limit the audience for her work. Toward the end of my research, a new problem with identity-specific funding categories emerged: the rise of “Pretendians.” As with other forms of race fakery, non-Indigenous artists and curators with dubious claims to Indigeneity were, and are, applying for and receiving Indigenous-specific funding, pulling resources away from Indigenous artists in what is an already very limited funding ecosystem. This has been incredibly damaging and painful for many of the people with whom I work, who are dismayed, as I am, at the persistence of the settler colonial desire to become Indigenous, and the ways that this has been enabled within the structures of limited government funding.

Frederick Alexcee, Txaldzap’am nagyeda laxa (c. 1886). Image courtesy of the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, BC. The sculpture was created as a baptismal font in a church at Lax Kw’alaams, a Hudson’s Bay trading post known formerly as Fort Simpson (1834–80). It is currently housed in the Museum of Anthropology. Created by Tsimshian carver Frederick Alexcee, it combines Christian imagery with Tsimshian formal conventions to show the influence of the missionaries.

What unique characteristics do you find with present-day Indigenous art and protests compared to art and protests of the 20th Century?

I’m going to give the easy answer first: digital worlds and social media have certainly made new kinds of connection possible across long distances and borders. We saw this with Idle No More, an ongoing Indigenous environmental and social movement that shaped the whole book, but particularly my analysis of a powerful performance and shaming ritual—a public ceremonial breaking of a large copper form called Taaw, which means “oil”—carried out by the Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick. Perhaps more familiar to US audiences, this connective spirit also animated the anti-pipeline protest at Standing Rock, which used art to mobilize aid and support for Water Protectors across vast swaths of the US and Canada.

I think it’s important to mention that content and tactics have shifted somewhat, away from an emphasis on recognition that Indigenous people are here and have unique rights, toward a conversation about sovereignty and what it means. For example, from where I sit as a settler—a political identity that many non-Indigenous people use to draw attention to the fact that they are not Indigenous, and in order to question what it means to live on stolen land—I have obligations to the sovereign Indigenous Nations on whose lands and waters I live and work. These relationships do not include presumed access to Indigenous knowledge and resources. I feel hopeful that as a result of activists’ emphasis on sovereignty, some of the empty “decolonizing” and “indigenizing” rhetoric is giving way to real, material change: Land Back movements, the prioritizing of hiring Indigenous scholars and artists in universities, and just a greater collective sense of what it means to acknowledge the Indigenous nations whose lands we continue to share and exploit. This is why, even though I continue to teach contemporary Indigenous art and do research on the Northwest Coast, much of my work has shifted to include more local applied efforts toward remediating environmental crises and practicing sustainable curating on New York’s coastline. This isn’t some eco-romantic vision of Indigeneity, but an insistence that “sustainability” has to include relationships with Lenape, Shinnecock, Haudenosaunee, and other Indigenous artists, and with urban Indigenous community organizations in the city.

What parallels are there between the most pressing issues for Indigenous artists in Canada and those of Indigenous people in the US?

I think immediately of the Indigenous-run galleries, dedicated studio spaces, and resources that continue to be pressing needs on both sides of the border; and something of relevance to all of these is the problem of mentorship: having folks to serve as art world Elders who can help emerging artists access these networks and connect with community. If I can mention something close to home, Professor Eve Tuck’s new Center CIRCL, which stands for “Collaborative Indigenous Research with Communities and Land,” is a hub right here at NYU that is working toward being this kind of research center— not only for art, but for all forms of Indigenous knowledge.

Repatriation of cultural belongings and improved access to museums is another shared issue of concern for many artists who want to learn from and care for older pieces that are often difficult to even visit because of the many barriers to accessing museum collections. This is obviously a thorny issue, because preservation and access can be at odds in the museum in ways that reveal real cultural differences in notions of care—for instance, one of the chapters of my book, about the repatriation of a totem pole from a museum in Sweden to the Haisla people in Kitimat, addresses how Indigenous understandings of care often includes relationships with nonhumans, in this case, the fish who return to the river following the pole’s return. Finally, because so much of the book’s political thread unspools from the legacies and promises of the TRC, I would call our attention to similar efforts that are underway in the US to grapple with the violent and assimilationist legacy of federal Boarding Schools. So much of what I have learned about repair has to do with the delicate balance of revealing truth, while taking care not to re-traumatize a community that has been grappling with these truths far longer than they have been in the wider public sphere. The work of repair should not become another coercive, settling mechanism, a competition over who can reveal the most or apologize the loudest; but rather, an ongoing process that retains its capacity to unsettle us still, creating unexpected alliances in art worlds and beyond.