Canterbury researchers have found that neither humans nor AI detection programmes are reliable or accurate for spotting the use of software used to manipulate online survey responses.

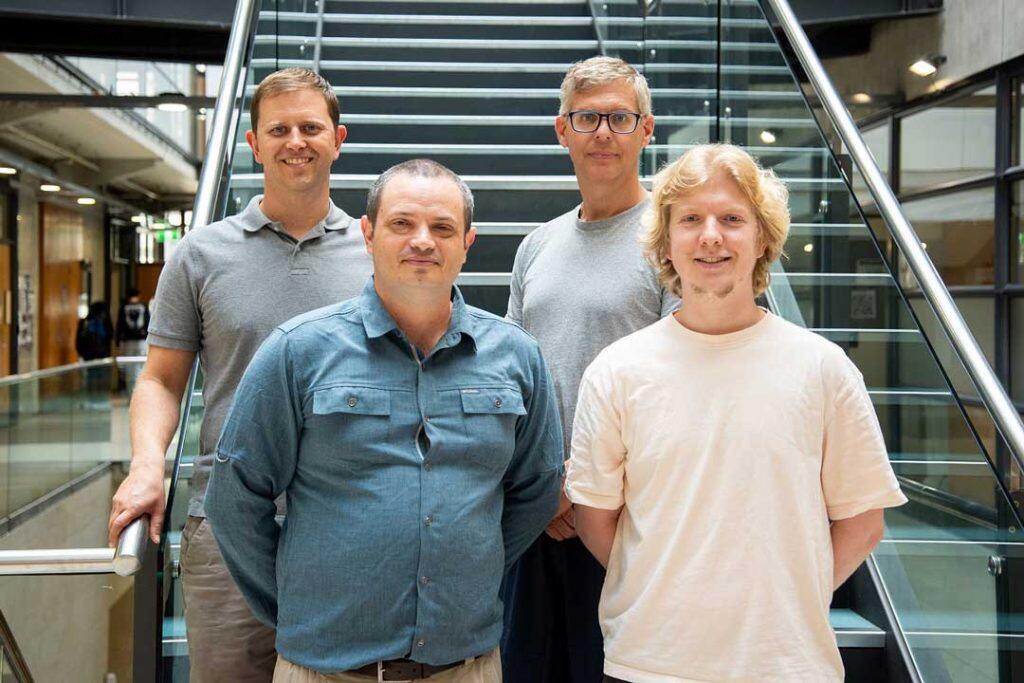

Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha | University of Canterbury (UC) Associate Professor Christoph Bartneck and his research team Dr Andrew Vonasch, Benjamin Lebrun and Sharon Temtsin, investigated the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and Gemini to complete online questionnaires.

LLMs have made it possible for bad actors to automatically fill in and therefore influence the outcomes of online surveys. The researcher’s goal was to find out whether people or AI detection systems can reliably spot the difference between humans and bots when it comes to online surveys that use crowd-sourcing platforms to recruit participants.

Associate Professor Bartneck says their research found that 76% of the time people could correctly identify whether the survey had been filled out by a human or AI. This is a poor result given there is a 50% chance they get it right just through guessing. AI detection tools performed much worse.

“The biggest danger is the hidden manipulation of our political and scientific processes. If a small number of bad actors can bias data collection, then the survey results are no longer representative and the foundation of the social sciences and public consultation is in danger,” says Associate Professor Bartneck.

Manipulation of surveys is not uncommon. Most recently Aotearoa New Zealand saw this with an American comedian manipulating the Bird of the Year results. While this was a bit of fun, the more dangerous side includes changing or influencing the results of government consultation without the public knowing.

While there are tools to prevent bots from filling in surveys or spotting a non-human generated response, the development of LLMs allows bots to get around those barriers.

“How many spam bots are out there that already exploit this? We don’t know this. It only takes one or two skilled people to spam this system with millions of responses.

“You can, if you write a script that does this, target millions and millions and millions of surveys. So, it doesn’t take much for a single person to falsify millions of survey responses.”

Associate Professor Bartneck says while this research shows the broader current and potential impact to society, he is also concerned for his work. “A lot of our data collection that we do for research could be compromised, so we are also very vulnerable to this, and there’s very little we can do about it right now. There is some self-interest in this study, as I’m scared about my own research.”

“If AI becomes too prevalent in submitting responses, the costs associated with detecting fraudulent submissions will outweigh the benefits of online questionnaires. Individual attention checks and open-ended responses will no longer be sufficient tools to ensure good data quality.

“This problem can only be systematically addressed by crowd-sourcing platforms. They cannot rely on automatic AI detection systems, and it is unclear how they can ensure data quality for their paying clients.”

More research is being done to build better detection systems, with one of Associate Professor Bartneck’s PhD students exploring whether LLMs can pass the Turing Test, which is designed to see if machines can think. It uses an imitation game in which a machine tries to trick a human to believe it is a human.