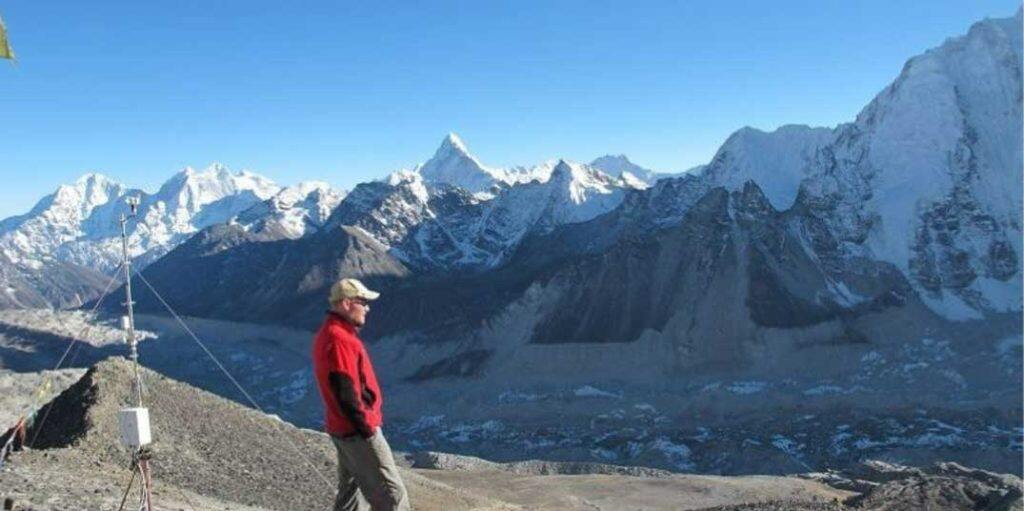

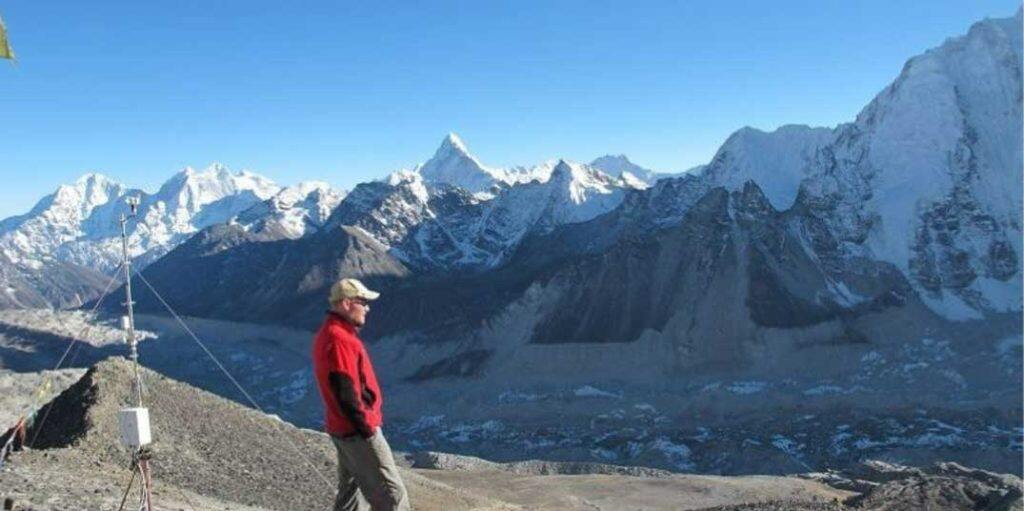

Climbing beyond Everest base camp to test if the snow high up on the mountain is melting is the latest challenge being faced by glaciologists at the University.

Despite air temperatures being well below zero on the highest mountain on Earth, it is believed that the snow may be thawing, threatening the water supplies of over one billion people below.

If the theory proves correct, it would suggest that the glaciers in the Himalayas are melting faster than expected due to rising air temperatures and intense solar radiation.

“We don’t know how the equipment will fare in such a harsh climate as could also be said of the human body!”

–Professor Duncan Quincey, School of Geography

Professor Duncan Quincey from Leeds’ School of Geography and researchers from Aberystwyth University, will lead a team to the Western Cwm, over six kilometres above sea level and half a kilometre above base camp.

They will go on their first trip in spring 2025 to drill into the surface of the upper reaches of Khumbu Glacier and use the boreholes to record temperatures. The team will also install automatic weather stations at the study sites.

This data will help them look for evidence of melting and refreezing within the glacier’s surface snowpack.

Scientific observations are rarely made at high altitudes because of the logistical challenges in transporting equipment.

The team is designing a new lightweight drilling setup to overcome these barriers. However, it will still face problems such as maintaining battery power in freezing temperatures and working in areas with harsh living conditions and low levels of oxygen.

“Our previous work has relied on helicopters to transport our equipment onto the glacier but given how thin the air is in the Western Cwm, we can’t be sure the helicopters will be able to fly this time,” explained Professor Quincey.

“We also won’t know how the equipment will fare in such a harsh climate as could also be said of the human body!”

The new project follows previous findings by the researchers which showed that the temperature of the ice in the lower parts of Khumbu Glacier, at the foot of Mount Everest, is warmer than would be expected given the local air temperature.

Glaciers in the highest mountains of the planet are an extremely important source of water with over one billion people – including many in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh – depending on Himalayan runoff.

Changes in the rate of glacier thawing would threaten this water supply. Another danger would also be more flooding from failures of natural ice dams, or so-called Glacial Lake Outburst Floods.

Professor Bryn Hubbard from Aberystwyth University’s Department of Geography and Earth Sciences said: “It may well be a bit of a surprise to many that snow is melting within the mountain’s Western Cwm, but it is increasingly likely, and it needs to be investigated and measured if we are going to be able to identify the effects of climate change on this water-stressed region and beyond.

“Understanding and recording what actually happens inside these glaciers is critical to developing computer models of their response to anticipated climate change.

“Equally important is developing a better understanding of how they flow so that we can better predict when dams that form on these glaciers are likely to be breached, releasing destructive volumes of water to the valleys below.

“This is a real risk in the Himalayas as it is in other regions such as the Andes and has the potential to endanger the lives of thousands of people.”

The researchers hope the work will give them a new understanding of processes and changes that are relevant for all glaciers in similar settings world-wide and indicate the extent to which other glaciers within the Himalayas may also contain unexpectedly warm ice.

Professor Quincey added: “If we can successfully drill even a single borehole within the Western Cwm, that will be a major success.

“Most importantly, it will lead us to being able to model how water supplies are likely to change for a large part of the world’s population with much greater certainty.”

The project is funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and is a collaboration between academics from the University of Leeds and the University of Aberystwyth.