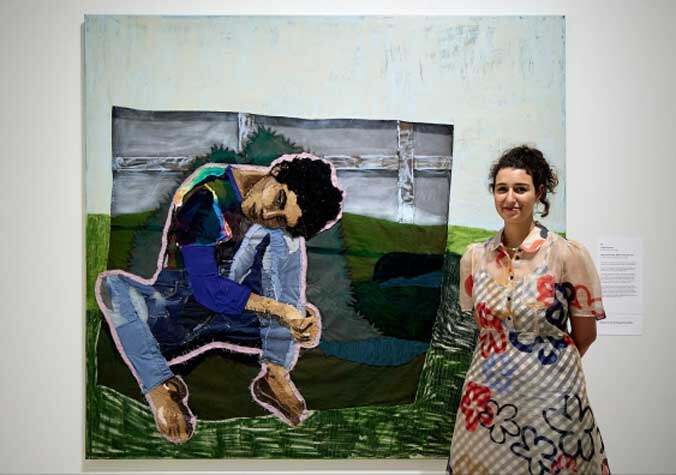

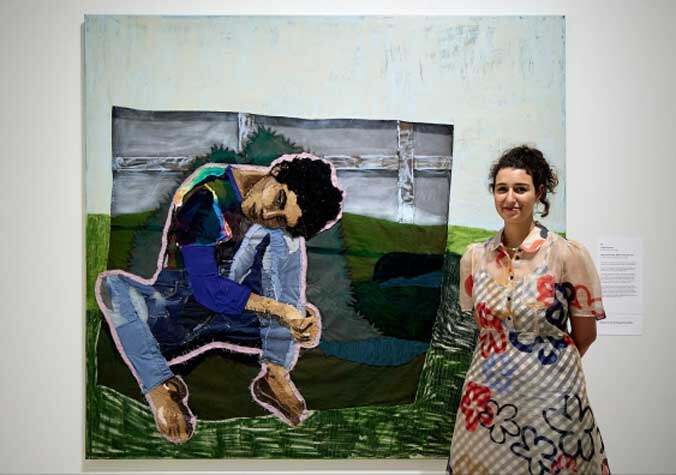

Archibald Prize winner Julia Gutman paints portraits whose stories run deep, and are layered with meaning and with textiles, too.

A long-held dream was fulfilled for Sydney artist Julia Gutman on May 5, when she was awarded the Art Gallery of NSW’s $100,000 Archibald Prize for her portrait of her friend, singer-songwriter Jessica Cerro (aka Montaigne).

As she accepted the award, Gutman said it was “a very insane and very unfathomable honour. I’ve dreamt about it since I was 12 years old.” Not necessarily winning, she clarifies later, but being part of it, a hope born from visits to the Archibald with her grandmother as a child.

Gutman, who is a UNSW graduate in Fine Arts (Painting) and a casual academic at UNSW’s School of Art & Design, is one of the youngest winners of the Archibald Prize at age 29. She is also only the eleventh woman to receive the prize in its 102-year-old history.

Gutman’s success could be seen to represent a shift in the kinds of portraits (and subjects) that are receiving attention and acclaim. “I’m so grateful to be working at a time where young female voices are heard,” she said in her acceptance speech, “and to really get to be part of a conversation that’s happening inside this gallery that speaks to the conversation that’s happening in this country.

“So much of my practice is devoted to revisiting and critiquing and contending with the histories housed in institutions like this one.”

The winning portrait

The painting, created in Julia’s unique style, which she has described as ‘painting with fabric’, is titled Head in the sky, feet on the ground. The background of the portrait is in oil, and Cerro’s figure is constructed using “found” fabric, which is sewn into the work.

The fabric is sourced from clothes, both her own, and pieces donated by friends and family, which means there’s a personal narrative embedded into each of her works.

The 2023 Archibald Prize winning portrait: Head in the sky, feet on the ground. Artwork © Julia Gutman, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jenni Carter

And while some describe her work as textiles, Gutman describes herself as a painter. “I really wanted to speak more directly to the history and language of painting,” she says.

Recently, Gutman has been choosing to compose her works referencing iconic poses of women in art history, and her Archibald Prize winning portrait echoes the composition of Egon Schiele’s 1917 work Seated woman with bent knees.

“I’m really interested in painting, and I’m really interested in paintings of women,” she explains. “And considering that most historical paintings in museums are by men, and a lot of paintings in museums are women, when you’re looking at the history of painting, you’re really looking largely at the way that men look at women.” Gutman’s question as she appropriates and riffs on iconic poses is “how do we notice the brilliance and artistry, and also acknowledge the pain and disgust?” Rather than writing off or ignoring the problems of the history of portraiture, Gutman seeks to engage with it. “I’m interested in the ways that we can revisit it, talk about it and engage with those histories.”

Engaging with history

In her 2022 solo exhibition, Muses, Gutman created a self-portrait called The Black Jeans, which was an appropriation of modernist painter Balthus’s painting The White Skirt. The White Skirt is a painting Balthus made of his wife, Antoinette. Gutman explains, “Balthus is iconically a problematic artist. He used lots of children as his models, a lot of who might not really have had a choice whether or not they were going to sit for him. The White Skirt is a painting of his wife, who he met when she was 12. The painting was made when she was 18, but we don’t really get to hear from her. We just see her and we look at her in the way that Balthus looked at her.” In her portrait, Julia has taken the pose, but inserted herself into the chair, wearing the clothes she wore making the portrait. And, she quips, “I look pretty annoyed.”

The Black Jeans © Julia Gutman. Photo by Simon Hewson, courtesy of Sullivan+Strumpf.

For her Archibald-winning work, Gutman and Cerro chose the pose referencing Seated Woman with Bent Knees together. “It’s a very androgynous kind of pose,” explains Gutman. “At the time it was really ugly and shocking. She’s on the floor in her undies. Her body is kind of distorted. It’s intimate, but it’s not particularly feminine. It felt reflective, not necessarily of Montaigne, but of Jess. It gets to be simultaneously a compositional love letter and historical critique.”

Gutman is one of the youngest women to take out the Archibald Prize. But how does Gutman think being a young woman affected her approach to the competition? “So much of being a young woman in the world is about claiming space. I think this is also true for those who don’t conform to the gender binary. And also being aware that people don’t take you seriously. Jess and I were so shocked to have won, and I think there was something freeing about assuming that we wouldn’t win because we really just went for it and did something that didn’t fit the brief at all.”

But as for commentary describing her work as maverick or disruptive, Gutman pushes back. “I genuinely just think I’m trying to be myself,” she says. “And I’m trying to do that as honestly as possible. I don’t like when things are controversial for the point of being controversial.” Gutman’s current practice authentically expresses the thoughts and feelings she wrestles with as she creates portraits. People can, and do, make of it what they will.

Gutman’s evolving practice

Gutman’s unique multidisciplinary style is a relatively recent practice. She studied painting as an undergraduate at UNSW Art & Design, and then went on to complete a Masters in Fine Arts (Sculpture) at Rhode Island School of Design in 2018.

The experience there – where she felt out of place because of her lack of experience working with wood and metal, and felt every time she had a question, “some guy would take the wood and do it for me”— led to a change in focus. “I wanted to make things that were really dramatic and big and all encompassing, and textiles became a way for me to work at scale. I was conceptually exploring how something can be grand and take up lots of space in a way that’s really soft.”

At first, Gutman looked at the materials very conceptually, thinking about what the item of clothing had to say about an era, or industry, or race and gender. But, she explains, “I was making this work that sounded interesting, and was interesting to other people, but it wasn’t actually what I loved. I love figurative painting, I’m a sensitive person, I love storytelling, I love my friends. I realised I was making work that if I had seen it, I might have walked past it.”

And then Gutman’s life was disrupted by the death of her studio mate and friend, and she made the decision to return to Australia. As Gutman worked through her grief her current practice of using textiles from clothing belonging to friends and family evolved. Her first works in this style were made using fabric from clothing that belonged to the friend who had passed away. “I think there’s a real relationship between loss and grief and textiles. I think that we really hold memory. It’s kind of the closest embodiment we have of the person outside the physicalisation of that person. You know, clothes take on our bodies, they smell like us. They express something about us because we choose them.”

The materials she uses are “all charged with memories. Some more so than others. So, while I’m working, I’m really thinking about everyone and remembering.”

Life as a Fine Arts student and teacher

A portrait of Julia in her studio. Photo by Maggie Shapter, courtesy of Sullivan+Strumpf.

Since returning from the United States, Gutman has also spent time teaching art at UNSW Art & Design, where she shares with students the best advice she ever got, which is “the work has to be its own reward”. And she expands, “if you love what you’re making, and want to devote time to it, it should be enough and everything else that happens externally is extra.”

Being a Fine Arts student is a special time, says Gutman. “Having the conversations that happen in the studio be taken seriously and really being allowed to give ideas space and think about the power of culture is really precious. It’s so rare to be in a room full of people who are listening to what you think and what you feel – and the core output is ideas. What a privilege.”

As for what’s next for Gutman, she won’t be teaching in second semester but is packing up her sewing machine and materials and heading to Italy as an artist in residence at Palazzo Monti, in Brescia. In November her works will be exhibited in Milan, and then she will be back in Australia preparing for her next solo exhibition, planned for March 2024.

And what difference will the Archibald Prize make to Gutman’s life as an artist? “I like to think of it as a job promotion,” she says. “Whatever happens externally, you still have to come to the studio and show up with yourself, and that doesn’t get easier because someone said that your work was good. But I would like to venture into other ways of working, making some videos and working at a bigger scale. This kind of opportunity gives you the power to do that. And particularly as a young woman to be taken seriously.”

Fortunately, the studio is one of Gutman’s favourite places to spend her time, as she’s certainly got a lot of creating to do. And a larger audience than ever.