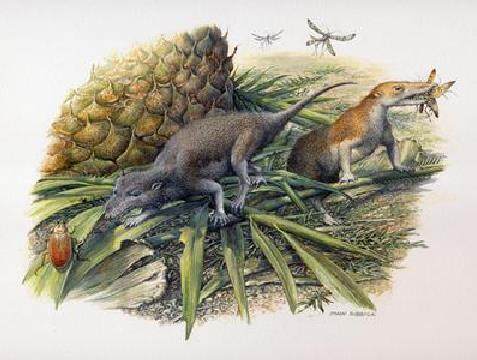

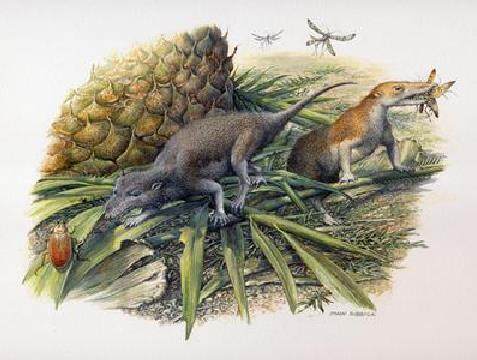

Pioneering analysis of 200 million-year-old teeth belonging to the earliest mammals suggests they functioned like their cold-blooded counterparts – reptiles, leading less active but much longer lives.

The research, led by the University of Bristol and involving scientists from University of Southampton, published today in Nature Communications, is the first time palaeontologists have been able to study the physiologies of early fossil mammals directly, and turns on its head what was previously believed about our earliest ancestors.

Fossils of teeth, the size of a pinhead, from two of the earliest mammals, Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium, were scanned for the first time using powerful X-rays, shedding new light on the lifespan and evolution of these small mammals, which roamed the earth alongside early dinosaurs and were believed to be warm-blooded by many scientists. This allowed the team to study growth rings in their tooth sockets, deposited every year like tree rings, which could be counted to tell us how long these animals lived. The results indicated a maximum lifespan of up to 14 years – much older than their similarly sized furry successors such as mice and shrews, which tend to only survive a year or two in the wild.

“We made some amazing and very surprising discoveries. It was thought the key characteristics of mammals, including their warm-bloodedness, evolved at around the same time,” said lead author Dr Elis Newham. Dr Newham, now Research Associate at the University of Bristol, led this study that was conducted during his time as a PhD student at the University of Southampton, supervised by Dr Philipp Schneider and by Dr Neil Gostling with Dr Pam Gill and Dr Ian Corfe from the University of Bristol and University of Helsinki respectively.

“By contrast, our findings clearly show that, although they had bigger brains and more advanced behaviour, they didn’t live fast and die young but led a slower-paced, longer life akin to those of small reptiles, like lizards,” he added.

Using advanced imaging technology in this way was the brainchild of Dr Newham’s supervisor Dr Pam Gill, Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol and Scientific Associate at the Natural History Museum London, who was determined to get to the root of its potential.

“A colleague, one of the co-authors, had a tooth removed and told me they wanted to get it X-rayed, because it can tell all sorts of things about your life history. That got me wondering whether we could do the same to learn more about ancient mammals,” Dr Gill said.

By scanning the fossilised cementum, the material which locks the tooth roots into their socket in the gum and continues growing throughout life, Dr Gill hoped the preservation would be clear enough to determine the mammal’s lifespan.

To test the theory, an ancient tooth specimen belonging to Morganucodon was sent to Dr Ian Corfe, from the University of Helsinki and the Geological Survey of Finland, who scanned it using high-powered Synchrotron X-ray radiation.

“To our delight, although the cementum is only a fraction of a millimetre thick, the image from the scan was so clear the rings could literally be counted,” Dr Corfe said.

It marked the start of a six-year international study, which focused on these first mammals, Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium, known from Jurassic rocks in South Wales, UK, dating back nearly 200 million years.

“The little mammals fell into caves and holes in the rock, where their skeletons, including their teeth, fossilised. Thanks to the incredible preservation of these tiny fragments, we were able to examine hundreds of individuals of a species, giving greater confidence in the results than might be expected from fossils so old,” Dr Corfe added.

The journey saw the researchers take some 200 teeth specimens, provided by the Natural History Museum London and University Museum of Zoology Cambridge, to be scanned at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and the Swiss Light Source, among the world’s brightest X-ray light sources, in France and Switzerland, respectively.

In search of an exciting project, Dr Newham took this up for the MSc in Palaeobiology at the University of Bristol, and then a PhD at the University of Southampton.

“I was looking for something big to get my teeth into and this more than fitted the bill. The scanning alone took over a week and we ran 24-hour shifts to get it all done. It was an extraordinary experience, and when the images started coming through, we knew we were onto something,” Dr Newham said.

Dr Newham was the first to analyse the cementum layers and pick up on their huge significance.

“We digitally reconstructed the tooth roots in 3-D and these showed that Morganucodon lived for up to 14 years, and Kuehneotherium for up to nine years. I was dumbfounded as these lifespans were much longer than the one to three years we anticipated for tiny mammals of the same size,” Dr Newham said.

“They were otherwise quite mammal-like in their skeletons, skulls and teeth. They had specialised chewing teeth, relatively large brains and probably had hair, but their long lifespan shows they were living life at more of a reptilian pace than a mammalian one. There is good evidence that the ancestors of mammals began to become increasingly warm-blooded from the Late Permian, more than 270 million years ago, but, even 70 million years later, our ancestors were still functioning more like modern reptiles than mammals”

“It was remarkable to be able to tell stories about the life history of these tiny mammals, which died 200 million years ago. Although it is not a new to suggest that these little creatures evolved their mammalian characteristics in a stepwise fashion, it is not necessarily expected that they evolved big brains before a faster mammalian metabolism,” said Dr Gostling, Lecturer in Evolution and Palaeobiology at the University of Southampton.

While their pace-of-life remained reptilian, evidence for an intermediate ability for sustained exercise was found in the bone tissue of these early mammals. Dr Schneider, Associate Professor in Biomedical Imaging at the University of Southampton explained: “Bone is a living tissue, containing fat and blood vessels, and the diameter of the canals comprising the vessels can tell us about the maximum possible blood flow available to an animal, critical for strenuous activities such as running.”

Dr Newham said: “We found that in the thigh bones of Morganucodon, the blood vessels had flow rates a little higher than in lizards of the same size, but much lower than in modern mammals. This suggests these early mammals were active for longer than small reptiles but could not live the energetic lifestyles of living mammals.”

Paper:

‘Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals’ by E. Newham et al in Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18898-4