Amultinational study led by Yale and including a University of Calgary research team provides the earliest evidence to date of ancient humans significantly altering entire ecosystems with fire.

The study, published on May 5 in the journal Science Advances, combines archaeological evidence with paleoenvironmental data on the northern shores of Lake Malawi in eastern Africa to document that early humans were ecosystem engineers. They used fire — as far back as 85,000 years — to prevent regrowth of the region’s forests, which created a sprawling bushland that still exists today.

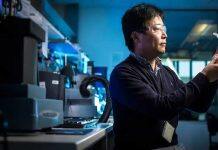

- Photo above: The Mercader SDS lab investigates human origins in East Africa, specializing in reconstructing the environmental context in which human activity occurs. The lab studies proxies including a silica precipitate produced by plants. These silica particles are degradation resistant and may persist buried in sediments for millions of years. They allow the recreation of the plant landscape. Professor Julio Mercader is seen here in the process of extracting phytoliths from ancient sediments.

“This is the earliest evidence I have seen of humans fundamentally transforming their ecosystem with fire. It suggests that by the Late Pleistocene age, humans were learning to use fire in truly novel ways. In this case, their burning caused replacement of the region’s forests with the open woodlands you see today,” says Dr. Jessica Thompson, lead author and assistant professor of anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Yale University.

Thompson authored the study with 27 colleagues from institutions in the United States, Canada, Africa, Europe, Asia and Australia. Thompson led the archaeological work in collaboration with the Malawi Department of Museums and Monuments, David Wright of the University of Oslo, who led efforts to date the study’s archaeological sites, and Sarah Ivory of Penn State, who led the paleoenvironmental analysis.

Study has significant UCalgary connection

Dr. Julio Mercader, PhD, professor in the Department of Anthropology and Archeology at UCalgary, extracted and examined some of the key evidence along with his team in the Stone Tools, Diet and Sociality (SDS) lab and served as a co-author on the paper. Specifically, he studied microscopic silica particles that reveal ancient plant landscapes.

Many scientists refer to our current time as the Anthropocene, or the period when humans became the single- most influential species on earth. With this new research, Mercader says the period in which humans have actively shaped and altered the environment stretches back further than previously understood, and could reach back further still.

“Human anthropogenic impact on the environment is really extreme today, and we are talking about the Anthropocene now and how we are degrading everything. But the reality is, this pattern has deep roots,” says Mercader.

He says this work was made possible through a transdisciplinary approach to the research. His own team includes expertise in technology, climate change, diet, plant life and human lifeways over long periods of time. The work his team did helped the international group of researchers understand what they were looking at when they drilled sediment samples from the bottom of the lake and compared them with those in archaeological sites along the shore.

Novel transdisciplinary approach

“It is the novelty of the approach and the unlikely combination of disciplines that makes the difference between traditional collaboration and high reward research in which geoscientists, environmentalists and policy-makers work together with archeologists,” says Mercader. “That this work is being used by others indeed speaks to the tremendous value that the University of Calgary sees in transdisciplinary work.”

The artifacts examined by the researchers were produced across Africa in the Middle Stone Age, a period dating back at least 315,000 years. The earliest modern humans made their appearance during this period, with the African archaeological record showing significant advances in cognitive and social complexity.

The three lead researchers discovered that the regional archaeological record, its ecological changes and the development of alluvial fans near Lake Malawi — an accumulation of sediment eroded from the region’s highland — dated to the same period of origin, suggesting that they were connected.

Lake Malawi’s water levels have fluctuated drastically over the ages. During its driest periods, the last of which ended about 85,000 years ago, it diminished into two small, saline bodies of water. The lake recovered from these arid stretches, and its levels have remained high ever since, according to the study.

The archaeological data were collected from more than 100 pits excavated across hundreds of square kilometres of the alluvial fan that developed during this time of steady lake levels. The paleoenvironmental data are based on counts of pollen and charcoal that settled to the floor of the lakebed and were later recovered in a long sediment core drilled from a modified barge.

Early people took control of their environment

Lead co-author Thompson says that researchers can only speculate on why people were burning the landscape. Possibly they were experimenting with controlled burns to produce mosaic habitats conducive to hunting and gathering, a behaviour documented among hunter-gatherers. It could be that their fires burned out of control, or that there were simply a lot of people burning fuel in their environment that provided for warmth, cooking or socialization.

“One way or another, it’s caused by human activity,” says Thompson. “It shows early people, over a long period of time, took control over their environment rather than being controlled by it. They changed entire landscapes, and for better or for worse, that relationship with our environments continues today.”

Human Origins in Action conference May 18-20

Julio Mercader will be a featured speaker in a three-day online conference, Human Origins in Action, organized by the University of Calgary, held May 18 to 20, 2021. The international conference will highlight the relevance of transdisciplinary work at the interface of science, human evolution and society.

Register here