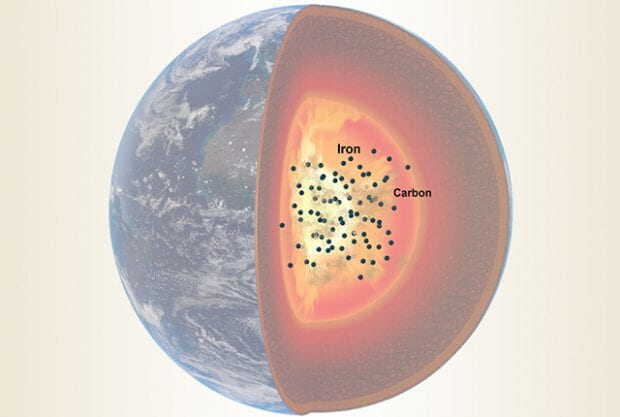

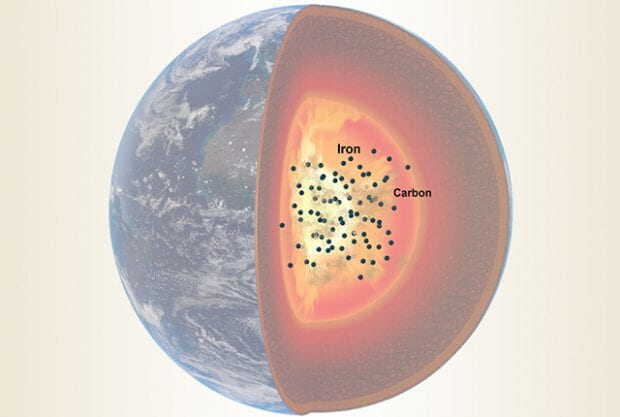

New research from Rice University and Florida State University suggests Earth’s core contains up to 95% of the planet’s carbon.

The study, published online this week in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, estimates Earth’s outer core is 0.3% to 2% carbon. Though the percentage is low, the outer core’s immense size puts the estimated weight of carbon between 6 million trillion tons and 41 million trillion tons.

“Understanding the composition of the Earth’s core is one of the key problems in the solid-earth sciences,” said co-author Mainak Mookherjee, an associate professor of geology in Florida State’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science. “We know the planet’s core is largely iron, but the density of iron is greater than that of the core. There must be lighter elements in the core that reduce its density. Carbon is one consideration, and we are providing better constraints as to how much might be there.”

Previous research had estimated Earth’s total carbon, but the new study refines those estimates, in part due to improved models that account for other light elements in the outer core like oxygen, sulfur, silicon, hydrogen and nitrogen.

Like hydrogen and oxygen, carbon is a life-essential element. It’s part of what makes life possible on Earth.

“It’s a natural question to ask where did this carbon that we are all made of come from and how much carbon was originally supplied when the Earth formed,” Mookherjee said. “Where is the bulk of the carbon residing now? How has it been residing and how has it transferred between different reservoirs? Understanding the total inventory of carbon is what this study gives us insight to.”

Rice co-author Rajdeep Dasgupta said, “There have been a lot of activities over the last decade to determine the carbon budget of the Earth’s core using cosmochemical and geochemical models. However, it remained an open question because of a lot of uncertain parameters on the accretion process and the building blocks of rocky planets.”

Dasgupta, Rice’s Maurice Ewing Professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, is also principal investigator of the NASA-funded CLEVER Planets project, a multidisciplinary effort to explore the range of ways life-essential elements can be brought together to produce habitable rocky planets.

Knowing how much carbon exists on Earth will help scientists improve their understanding of the composition of both our planet and rocky planets elsewhere in the universe.

Because humans can’t access the Earth’s core, they have to use indirect methods to analyze it. The research team compared the known speed of compressional sound waves traveling through Earth to computer models that simulated different compositions of iron, carbon and other light elements at the pressure and temperature conditions of Earth’s outer core.

“When the velocity of the sound waves in our simulations matched the observed velocity of sound waves traveling through the Earth, we knew the simulations were matching the actual chemical composition of the outer core,” said lead author and Florida State postdoctoral researcher Suraj Bajgain.

“What is neat about this study is that it provides a direct estimate on the present-day carbon budget of Earth’s outer core,” Dasgupta said. “Therefore, this will in turn help the community bracket the possible planetary ingredients and the early processes better.”

The National Science Foundation (NSF) and NASA supported the research, and computing resources were provided by NSF’s Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment and Florida State’s Research Computing Center.